- Home

- Jan Coates

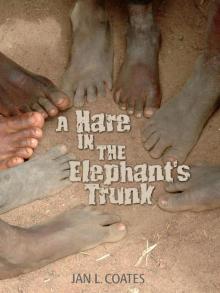

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk Read online

A Hare

IN

THE

Elephant’s

Trunk

JAN L. COATES

COPYRIGHT © 2010 JAN L. COATES

Epub edition copyright © June 2011

5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of Red Deer Press or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency), 1 Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, ON M5E 1E5, fax (416) 868-1621.

By purchasing this e-book you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any unauthorized information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or herinafter invented, without permission from Red Deer Press.

PUBLISHED BY

Red Deer Press

A Fitzhenry & Whiteside Company

195 Allstate Parkway,

Markham, ON L3R 4T8

www.reddeerpress.com

EDITED BY PETER CARVER

Cover and text design by Jacquie Morris & Delta Embree, Liverpool, NS , Canada

Printed and bound in Canada

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge with thanks the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Ontario Arts Council for their support of our publishing program. We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) for our publishing activities.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Coates, Jan, 1960-

A hare in the elephant’s trunk / Jan L. Coates.

ISBN 978-0-88995-451-9

eISBN 978-155244-290-6

1. Deng, Jacob—Juvenile fiction. 2. Refugee children—Sudan—Juvenile fiction. 3. Sudan—History—Civil War, 1983-2005—Refugees—Juvenile fiction. 4. Sudan—History—Civil War, 1983-2005—Children—Juvenile fiction. I. Title.

PS 8605.O238H37 2010 jC813’.6 C2010-904506-8

PUBLISHER CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA (U.S)

Coates, Jan L.

A hare in the elephant’s trunk / Jan L. Coates.

[256] p. : cm.

ISBN : 978-0-88995-451-9 (pbk.)

eISBN 978-155244-290-6

1. Sudan – Refuges – Juvenile fiction. I. Title.

[Fic] dc22 PZ7.C63847Ha 2010

To lost children everywhere,

struggling to find their way home ...

Wadeng ...

And to Don, Liam, and Shannon;

without you, my writing life;

would have remained a dream.

In 1983, civil war erupted in Southern Sudan, pitting government soldiers from the Muslim North against rural villages in the Christian and Animist South. In the 1980s and early 1990s, villages were ransacked, and up to two million Sudanese people were displaced. Among them were more than 20,000 young Sudanese boys, “The Lost Boys,” who walked in desperate conditions for many months and years, seeking refuge in Ethiopia and Kenya. This novel is inspired by the courage and determination of one of those boys, Jacob Deng, who was seven years old when war changed his life forever.

CONTENTS

Prologue

Book I

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Book II

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Book III

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Book IV

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Book V

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

INTERVIEW WITH JAN COATES

INTERVIEW WITH JACOB DENG

GLOSSARY

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Prologue

KAKUMA REFUGEE CAMP, KENYA, 1992

Jacob held his pointer finger just above his thumb, forming a small, rectangular box in the air. He closed one eye, held the box up to his open eye, and trapped puny little Majok in the frame. Holding his hand steady, Jacob slowly moved his finger and thumb closer and closer together, squishing his old enemy, like an ant, until Majok completely disappeared from view. Jacob sighed. If only it was that easy to get rid of him, he thought, shoving his hands deep into his pockets. If only I was an elephant, I could squash him with one foot. If only ...

They’ve both been trying to destroy me since I was seven; the war and Majok. I am twelve already; how old will I be before they finally leave me alone?

Jacob turned away from the shouts and laughter of the soccer field and walked slowly, scuffing his feet in the dirt between the winding rows of ramshackle shelters, until he found his own tent. He put the porridge water on the fire to boil, then dug his storybook out from under his mat. Flipping through its warped pages, he struggled to sound out some of the English words, tried to make them fit in with the black and white pictures. When he heard Oscar and Willy coming home from soccer, Jacob quickly buried the book beneath his mat again.

After supper, as he did most evenings, Jacob climbed to the top of a small scrub tree on the outskirts of Kakuma, his home for the past year. The tree had been picked bare of its thorns, and it was only a little taller than Jacob. He looked all around the camp, his eyes searching for Mama’s blue dress. Before the war, he would climb the giant baobab in Duk, watching for Mama when she’d been gone too long. As the first stars appeared in the blue-gray evening sky, he strained to hear them singing. Mama always said the stars sang her to sleep at night. Five years—how have I survived for five years without Mama?

A sudden flash of light caught Jacob’s eye. He looked down to see a small spot glowing on his bare arm. A firefly ... when we were little, Oscar and I used to chase them around Duk, like kite hawks. But they always preferred my big sisters for mates, landing on their strong, black Mama arms and hair, sparkling like jewels. Jacob smiled at the memory.

He gently scooped up the tiny insect and giggled as its wings tickled his cupped palms, glowing white in the warm light. How can such tiny things do something so magical—without fire! I wish I was a giant firefly—I would shine my light all over Sudan. Oscar could come with me—of course, his light would be the best and the brightest. I know we could find Mama, Grandmother, and my sisters, Uncle Daniel, Monyroor, Oscar’s family and Willy’s—maybe we could even visit Papa up in Heaven ...

Jacob set the firefly down carefully on a curled-up leaf. “Go find Mama for me,” he whispered. The insect crawled to the leaf’s edge, then flickered up, and disappeared, like a shooting star, into the darkening sky. Looking around, Jacob saw hundreds of people, but no blue dress, no Mama. He leaned back against the rough, gray branch, let his head fall forward, and pressed his fingers to his skull. Jacob rubbed his head, opening and closing his fingers, long, bony, Papa fingers. I don’t want my memories to be buried—I know they’re in here somewhere, but they’re getting too hard to find ...

BOOK I

Chapter One

DUK PADIET, SOUTHERN SUDAN, OCTOBER 1987

From the gnarled branches high in the leafy baobab, Jacob saw Mama kneeling by the river. Even in the blue-gray dusk, with the sun glowing red on the horizon, he could see that she was the most beautiful of all the mothers, like a queen with a crown of braids. Her slim, graceful arms dipped into the water over and over again. She stood, piled the wet clothing on her head, then began walking back toward the village, her blue dress dancing about her long, gazelle legs.

“Hello, Mama!” Jacob called out, scrambling awkwardly down from the tree to meet her, his hands cupped together. “I have something for you.”

“For me, Jacob?” Mama balanced her wet bundle with one hand and held Jacob’s cupped hands with the other. She smiled at her small son. “What can it be?”

Jacob giggled. “It tickles. That is your hint.”

“Is it a chicken feather? A butterfly?”

“Even better. Look.” Jacob opened his hands a tiny crack. Mama leaned over and peered into the opening.

“Ah, a firefly. The brightest of all God’s creatures. Such a plain-looking creature on the outside, but brilliant and magical inside when its warm spirit glows. What should we do with it?”

“We could use it to light up the hut,” Jacob said. “But I think fireflies don’t like to be indoors. They like to be free, like boys.”

“I think you are right.” Mama nodded her head. “So ...?”

Jacob held his hands high above his head and then opened them. The firefly lingered for a moment, then flashed away into the darkness.

“Thank you, Jacob. That was a wonderful gift.” Mama stroked Jacob’s fuzzy head. “Be a good boy now and sweep the mat for me?” Jacob hurried to do as she asked. Mama lowered her bundle to the mat, then began draping the clothing over the line stretched between their hut and a tree. She hummed as she worked.

“And what trouble have you been finding today, my son?” Mama took the mat Jacob handed her and added it to the colorful line.

“No trouble, Mama—but see here, I have made a cow for you, too.” Turning over the pot he’d hidden it under, Jacob held up a small brown cow made from clay. “The horns were hard to do,” he said, frowning. They were still not right—a little crooked and a bit too short. “It’s not dry yet.”

“This is your best cow yet! We have a whole herd of small cattle now.” Mama cradled it in her long, slender fingers and smiled as she held it out for Jacob’s two younger sisters to admire.

“It will soon be time for you to have your own big ox, like our brother, Kuanyin,” Abiol teased. She was Jacob’s secondoldest sister, and she was tall and graceful, like Mama. The eldest, Adhieu, was married and lived in her husband’s village a half-day away.

“Not for at least six more years,” Jacob answered. “I have only had seven birthdays!”

“Could you please put this on the high shelf with the others, Abiol?” Mama asked.

“Be careful! That took me a very long time,” Jacob warned her. “Don’t let Sissy carry it.”

“Yes, sir! Now if he could only learn to make these cows give milk!” Abiol took the clay figure into the hut. She was five years older than Jacob, and firmly believed their mother was spoiling her youngest son.

“They are too young for milking,” Jacob called through the doorway. “And they are boys!”

When Abiol returned, she and Sissy went to tend to the goats before supper. “We are coming. Stop your noise,” they called to the bleating goats.

“Be sure to give extra maize to Jenny,” Jacob shouted after them.

“Yes, sir!” Abiol answered.

“I have a gift for you, also.” Mama put her hand inside a pocket of her dress. Keeping her hand closed, she held it out to Jacob. “Guess what it is!”

“Is it a frog? Or a lizard? Ummm ... a fig?” He tried to peek inside her tightly-closed fist. “A beetle?”

Mama turned her hand over and Jacob pried open her fingers. It was a stone, the same blue as Mama’s dress, and it was shaped almost like a heart. “Where did you find it?” he asked excitedly. “Is this treasure for me to keep?” Jacob rubbed his fingers over its cool, smooth, marbled surface, then held it against his hot cheek.

“Of course. Keep it in your pocket. If you are ever missing me, it will bring me close to you. When you touch the stone, I will know you are thinking of me. I will also think of you.” She pressed her hand against Jacob’s heart. The boy giggled.

“I hardly ever miss you; just when you’re gone to the river for a very long time.” Jacob skipped off to show his sisters the treasure. As he turned the stone over in his hands, he looked back to where Mama stood by the hut. At the same time, she looked up and waved to him. It really works! It must be magic!

After the clothing was hung to dry, they began preparing food for the family. Jacob crouched beside Mama, watching as her strong hands easily ground the millet into the fine powder that would become their supper porridge. Jacob nodded his head and rocked back and forth to the steady rhythm of her heavy gray grinding stone.

Sissy clapped her pudgy hands and shook her head from side to side. “It’s like music!” Her pigtails stuck out in all directions, like the legs of a furry dancing spider.

After the meal, while Abiol was busy with her friends, Jacob and Sissy curled up together on Mama’s lap beside the fire. Jacob loved this time of day more than anything. “How do the stars stay up in the sky, Mama?” he asked. “And how far away are they? Can you really hear them singing?”

“Are they friends with the fireflies?” Sissy asked. “Do they play Seek and Find in the night?”

Mama laughed and shook her head. “I can hear them singing, but only when I am almost asleep. I have no answers for your other questions. You must one day go to school to find out—that and the answers to all your other questions!”

“But I don’t want to go to school. I just want to play and help look after the goats and go to cattle camp and wrestle when I’m bigger,” Jacob answered. “And I think you would miss me too much.”

“Sissy go to school, too?” Sissy asked.

Mama bent over them, her long neck arching gracefully, like a crane. She kissed the tops of their heads. “Ah, but you must both go to school. An education will give you the tools to carve a better future for our people.” Jacob looked up at his mother. She did not often use such a serious voice. Her long face, which people said was so like his, was not smiling as it usually was. “It is important to have big dreams and follow them. If your papa was still here, that would be his wish for you also.”

“But my dream is to be the best wrestler in all of Sudan, like Uncle Daniel. Or maybe I will be a soldier. I will not need to go to school,” Jacob insisted.

“With knowledge will come peace. With peace and knowledge together, Southern Sudan will be able to grow stronger. Wadeng, Jacob; Wadeng. Look always to tomorrow—it will be better, especially if young people like you go to school. You must always dream of a better tomorrow.”

“But today is good,” Jacob said quietly, tucking his small hand into hers.

“People are fighting all around us,” his mother replied, her voice tinged with sadness. “We have been lucky war has not yet found Duk Padiet. Now, get to sleep, my little monkeys—tomorrow will be here soon enough ...

Chapter Two

“Walk faster, Sissy. You are like a baby turtle.” Jacob stopped, then turned around to glare at his little sister, who was staring at a butterfly on her finger.

“Look, Jacob. A rainbow butterfly! It’s my lucky day,” she said, beaming up at him. Jacob’s glare turned to a reluctant grin.

“Why don’t you give her a ride?” Mama helped Sissy climb onto Jacob’s back. “You have the long feet of a hare, and the strong legs, too. Sissy is only little, Jacob. Have patience.”

“But I want to see Oscar. We have many things to do. I haven’t seen him for a very long time,” Jacob said. “Don’t s

queeze so hard, Sissy—I do not have the neck of a bull. Why couldn’t Abiol have come? Sissy is too heavy for me.”

“And who would care for the goats then, Jacob? And the chickens. What about Grandmother? It was your choice to come with us.”

“Only to see Oscar and Uncle Daniel,” Jacob said.

“I am also anxious to arrive, Jacob. My brother’s wife, Abuk, is heavy with child, and I must help with her birthing song.” Mama closed her eyes and began to sing.

Come out little baby, come into the world.

Your Mama is working; your family is waiting.

Come out little baby, sweet baby child.

She put one arm around both children. “Do you remember that song, Jacob?”

Jacob rolled his eyes. “Mama, I was not even born yet. How could I remember it? I was too busy working to get out!”

“I remember it, Mama!” Sissy was always eager to please.

“Of course you do,” Jacob answered. “You have the memory of a baby elephant—and you are as heavy as one, also!”

They arrived at the neighboring village just as the light began to fade. Oscar came running to greet them. “Where have you been?” He grabbed Jacob’s arm and pulled him away. “I’ve been waiting forever!”

“Sissy is too slow. She is only little, Oscar. Not like her big brother, Jacob the Hare. Want to race?”

As the two boys tore off across the compound, Jacob’s long legs made it impossible for Oscar to catch him. “But ... I ... am ... still the best soccer player,” Oscar said, puffing as he finally caught up to his friend.

“We will find out tomorrow,” Jacob said. “I have made a fine new ball. I will show you in the morning, when Mama takes it out of her bundle.”

As dusk arrived, the boys organized a game of Seek and Find. Majok immediately took over the organizing of the game. He was only a little older than Jacob and Oscar, but he had recently been away at school in Juba. “I will be the Finder first because I’m the only one who can count all the way to one hundred.”

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk