- Home

- Jan Coates

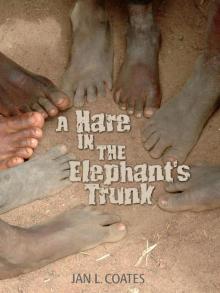

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk Page 23

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk Read online

Page 23

What was there about meeting Jacob that persuaded you there was a potential book in that moment?

It’s difficult to put it into words, but Jacob has a certain presence, inner peace, and sincerity that immediately drew me into his story. Within the safe confines of my local coffee shop, this stranger, this gentle giant, was able to take me someplace I had never been, nor even imagined being, before, and I could clearly see him as a small, lost boy of seven, longing for his mother as he made his way through the trauma of war. I can still picture our initial meeting vividly; I cried as he lovingly described the close bond he had shared with his mother. I was particularly struck, as a mother myself, by his continuing sadness at the loss of his mother, even as an adult. I was in awe that he wasn’t destroyed by the horrors he’d lived through, but rather was using his experiences to grow and become an incredibly strong person. His passion and commitment to raising funds and returning to Southern Sudan to build a school in his village stayed with me for many days after our meeting, and I wanted to do something to help. I knew for certain his story was one that would also have a longlasting effect on young readers.

Why did you decide to write this as a novel, rather than a biography?

By the time of our first meeting, twenty years had passed since Jacob had left Duk Padiet. Exact details and conversations would have been impossible to recapture at that distance of time and memory. Jacob was (is) a busy university student with a wife and two young children, and I knew the time he could spend with me in the writing of this book would be limited. The facts of Jacob’s journey formed the skeleton of the book, but the rest is the product of my research and imagination.

How much did you know about life in Sudan before you met Jacob and started working on this project?

I’m embarrassed to admit I knew nothing about Southern Sudan prior to my first meeting with Jacob. The biggest struggle for me was imagining his life as a small boy, a victim of war, alone in a part of the world I’ve not yet had a chance to see. Everything I included in the novel was outside my own realm of reference—I had to work hard to come up with descriptions that would be true to life in eastern Africa; life in Jacob’s village and in the refugee camps was just so completely different from my own life experience. While Jacob was walking to Ethiopia, I was newly married; while he was walking to Kenya, I was cocooned with my first child and oblivious to the Lost Boys and pretty much everything outside my home. Quite honestly, one of the reasons I was interested in writing this book was because I’ve always wished (in vain) I’d been brave enough to volunteer my time in Africa; it’s my hope that in some way, this novel may do some good in my stead— perhaps in raising awareness of, and support for, Jacob’s foundation (Wadeng Wings of Hope) through which he is raising funds to build a school in Duk Padiet.

Does knowing Jacob and writing his story make you want to do more books like this—novels based on the lives of real people?

While I was in university, I took several history courses; doing research for papers was something I enjoyed. The challenge of digging for pertinent information still appeals to me, but secondary sources aren’t nearly as valuable as primary ones. It truly was such a privilege for me to have Jacob share his story with me; hearing about the events in his own words, feeling the emotion in his voice as I listened, playing back my recording of his voice, helped make the situation he had lived through very real for me as I wrote. I’m a great admirer of the work of Deborah Ellis—she’s written a number of novels for young readers inspired by the lives of real children living in crisis. I actually wrote her a letter upon starting this project, seeking her advice, and she very kindly wrote back to me promptly with some suggestions. I would love to write another such novel, but Jacob’s story came knocking on my door, so to speak, and I wonder if, among the countless stories in the world, that might happen for me again. Time will tell. The manuscript I’m working on now is complete fantasy, which I have to admit is more pure fun, and less of a mental workout! I seem to always have too many ideas and too little writing time.

What is the most important thing you want people to take away from reading Jacob’s story?

Jacob and I have chatted about this topic, and I think we’re in agreement. It’s my hope that children struggling with troubles of their own will read about young Jacob, admire his determination as he worked to overcome the tremendous adversity in his life, and be inspired, and perhaps empowered, to confront and overcome their own problems. I would love young readers to walk away from this novel thinking and believing: If he could survive all that, then surely I can survive all this. Reading about children elsewhere helps expand young readers’ awareness of the world outside their own. It would be amazing if some young readers became interested in Africa after reading Jacob’s story and later went on to volunteer their time working there as young adults.

What advice do you have for aspiring young writers?

It’s not very original, but my most basic advice would be read and write—all the time. I have a clear memory of getting my first library card at the age of five—I’ve been a reader and a writer since then. Never accept that what you write down the first time is the best you can do— there’s (almost) always room to improve your writing, and that takes lots of practice and patience. I use a writer’s notebook—there are constantly gems to be mined from everyday life—if you have a memory like mine, those gems soon disappear unless they’re written down. When I visit schools, I describe myself as nosy. I’m always interested in what’s going on around me— you never know when the next great story idea will unexpectedly present itself. Keep your eyes and ears wide open! Writing is a most wonderful thing—you’re limited in what you can create only by the size of your imagination; there are constantly new worlds to be invented and explored.

INTERVIEW WITH JACOB DENG

Very briefly, how did you end up in Canada?

I came to Canada in 2003 through the Canadian Government program called Refugees Resettlement. After living in a refugee camp in Ethiopia for three years and twelve years in Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya, I needed to find a way to improve my life. I was told that Canada could provide me with better opportunities. Because many refugees wanted to come to Canada, this was not an easy process.

How are the people of your home village of Duk Padiet faring today? Are they still in danger?

The people in Duk Padiet are still in danger while peace is being enjoyed in other parts of the country. The problem that my people face is the lack of basic needs. They live their lives without access to things like food, water, health care, security, basic education, and infrastructure (roads, etc). In addition to this there has been violent tribal conflict between the people of Duk Padiet and the surrounding neighbors like the Nuer Tribes. Their attacks on Duk Padiet people have been because of their need for access to natural resources. This is why Wadeng is building a school in Duk Padiet. By educating the youth and the local members of the community we can change their love and respect for themselves, and they will be able to focus on the future of their children and the well-being of their community without fear of violence.

Have you been able to maintain contact with some of the boys you met during the years you were walking through your country to Ethiopia and Kenya?

We started living together when we were small children and so these men are like brothers to me. When you are without your family, you depend on those around you. Because of our strong bond many of us have stayed in contact with each other. Some of them are here in Canada, while others are in the U.S., Australia, Kenya, and South Sudan. Some are doing development work, like I am, in their home village. However, because this means reliving the difficult past, others have moved on to continue their education or start families of their own.

Why do you think your story—which focuses so strongly on the ill-treatment of children— touches such a wide range of readers?

I have been through a great deal of hardship in my life, but I always tried to see it as an oppo

rtunity to better myself. I did this through hope that tomorrow would be different and by not giving up when I was down. Unfortunately, this world is full of children who have been mistreated or abused. In this way, my story is comparable to that of others. I believe that although the details of my story are unique, the heart of the issue is true to many. Whether a person has lived through hardship at a young age or has had a happy childhood, by reading a story like mine, people will feel the need to do what they can to make change. Children are a precious part of any community, and each of us knows instinctively that healthy and happy children make for a better world.

In my lifetime, I have put all of my energy toward the betterment of the lives of children. I strongly believe that no child should ever have to go through what I have been through. There are children who are living their lives without the freedom of a childhood. They are, in a sense, living lifelessly. I know this pain and I am working hard to contribute to a solution to this problem. I think that the hurt I have been through and the passion I am working with now comes through in my story as an inspiration to others. This is why I stand as a voice for children who are in trouble and why I try to motivate people to help make their world more promising.

You have gone through incredible and terrifying experiences in your life. Have all these experiences made you a pessimist or an optimist?

My experience has given me a positive outlook on life. At the same time I know that things are not easy.

At a young age I made a conscious decision not to let this stop me because I discovered that if you don’t try things nothing will change. The outcome may be positive or negative, but life will go on regardless. I would have to say that I am certainly an optimist.

Tell me about Wadeng Wings of Hope and what you are trying to do through this organization.

My hope for Wadeng is that through a growing literacy program there can be emerging peace in South Sudan. Building a school is the first step toward a transformation in the infrastructure of the community. I believe that positive changes in social, religious, and political institutions will follow naturally and remove the barriers to economic development.

For more information on Jacob’s foundation,

Wadeng Wings of Hope, go to www.wadeng.org.

GLOSSARY

Abaar: orphan

Aci boot: a term used for the dead

Anyok: a Dinka game similar to field hockey

Calabash: a hollow gourd used as a container for liquids

Cieng: a Dinka word used to describe the security of living in peace and harmony

Dinka: a pastoral people living in the Nile valley of Southern Sudan; in their language, Dinka means “people.”

Etaba: a Turkana word for smoking, tobacco

Gaar: a series of six horizontal scars carved in the foreheads of young Dinka males as part of their initiation into manhood

Ghee: butter

Haboob: dry dust storm

Heglig tree: also known as desert date tree; a flowering tree, the blossoms and berries of which have medicinal characteristics

Kak: a Dinka game wherein several stones are laid out in a row. Another stone is tossed into the air, and the object of the game is to grab as many from the ground as possible without allowing the one in the air to hit the ground

Khawaja: white man

Kisra: a type of pancake

Kudu: a type of African deer

Laban: a type of sweetened milk

Luak: a type of hut used as a barn

Lulu tree: shea nut tree

Mancala: a strategy game using beans or pebbles and hollows in the dirt to form cups

Manna: the sweet substance found inside the seed pods of the tamarind tree

Muti: medicine

Ruel: the wet season, usually between July and October

Souk: marketplace

SPLA: Sudan People’s Liberation Army

Toc: a period of time when young men would eat meat and drink milk in order to make themselves fat and strong for upcoming wrestling matches

Tukul: a storage hut

Wadeng: a Dinka word meaning look always to tomorrow; it will be better

Wech: a song to encourage a bull to grow stronger

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Writing a novel, I’ve discovered, is a most collaborative undertaking, and I’d like to recognize the enormous contributions and support of the following people:

First and foremost, thank you to Jacob Deng, a gentleman of grace and integrity for whom I have the utmost respect and admiration. Although this book is not biographical, but rather inspired by your story, the bones of the story are undeniably yours. It has been a privilege and an honor to have you share the sometimes painful memories of your boyhood with me; I hope I have handled them with the care and dignity they deserve. May stepping stones continue to emerge for you as you pursue your career and the work of your foundation, Wadeng Wings of Hope (www.wadeng.org). Your mama would be so proud of you and your family.

Thanks also:

To Peter Carver—your phone call from Port Joli, upon reading my manuscript, is the highlight of my writing life to date. Thank you for believing in Jacob’s story and helping ensure it’s the best book it could be. Your enthusiasm, intelligent insights, guidance, and reassurances helped me gain confidence, both in this book, and in myself as a writer. Thanks especially for allowing me to be part of your community of writers in Port Joli; I’m sure your fish house was the birthplace of my writer’s soul! Thanks, as well, to the entire team at Red Deer/Fitzhenry & Whiteside, for your diligence in producing this book.

To Gary L. Blackwood, mentor extraordinaire, who, in four months, taught me pretty much everything I know about constructing and developing a novel. Your wisdom, allseeing eyes, and thoughtful suggestions were invaluable in the evolution of this book. Our time at the Fair Trade Café enabled me to turn Jacob’s story into a novel, and to grow as a writer, more than I could ever have imagined.

To Jane Buss and the Writers’ Federation of Nova Scotia, for nurturing my writing life and giving me a Mentorship to work on this novel with Gary Blackwood in the winter of 2009.

To the following authors, whose books I used in researching this novel: Dave Eggers, What is the What?; John Bul Dau, God Grew Tired of Us; Francis Mading Deng, Dinka Folktales, African Stories from the Sudan and The Dinka of the Sudan (the source of the poignant songs in this book); and Nick Greaves, When Hippo was Hairy, and Other Tales from Africa. Thanks also to Noah Pink for his moving documentary detailing Jacob’s return to Southern Sudan in 2005, and to the creators of, and contributors to, the countless Web sites I scoured in researching The Lost Boys.

To my friends and family, especially my gorgeous sister, Nancy Jennings, for listening to me talk endlessly about writing, and my neighbor, Karen Duncan, for copious cups of green tea, cookies, and caring.

To Kathy Stinson, who read so carefully the initial miniversion of Jacob’s story. Your detailed comments and suggestions helped me begin growing the manuscript.

To the Nova Scotia Department of Tourism, Culture, and Heritage, which provided me with a grant to attend the Carver-Stinson Writing Retreat in Port Joli in 2008.

To librarians, teachers, and booksellers everywhere—thank you for encouraging young readers to become book lovers.

To my parents and grandparents: thank you for sharing your sense of wonder, curiosity, and love of books with me, and for always believing in me. I hope you’ll get a chance to read this book; can you hear the stars singing over Nova Scotia?

And, finally, to Don, Liam, Shannon, and Bailey—thank you for putting up with me and my constant laptop companion, and loving me anyway; knowing you’re always there makes everything possible.

Jan L. Coates

Wolfville, Nova Scotia

April 2010

you for reading books on Archive.

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk