- Home

- Jan Coates

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk Page 9

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk Read online

Page 9

“Look around you.”

Everywhere, boys were busy gathering sticks, bits and pieces of paper, and other material they’d found. Jacob, Oscar, and Willy got right to work, scurrying around the camp, looking into every corner for anything they might use.

“It will be like the houses we used to build in the woods,” Jacob said.

“Except this isn’t just for fun.” Oscar tried to balance a bundle of sticks and scraps on his head.

“Here is a big—I don’t know what,” Willy said, pulling it out from under a pile of empty white sacks. “It doesn’t look like it came from any animal I’ve seen.”

“It is something made by men—it is plastic,” Monyroor said.

“Good work, Willy,” Jacob said. “It looks like it will keep out the rain.”

“We will build the strongest tent ever,” Oscar boasted. “Not even a tornado will hurt it! Not even an elephant or a big, fat hippopotamus.”

“Remember the clay villages we used to build?” Jacob asked.

“They were also the strongest,” Oscar replied, clenching his fists as he tried to make the muscles pop out of his scrawny arms. “We are master builders.”

Majok hurried by with a towering armload of building supplies. “Ha ha ha ...” he snorted. “Don’t make me laugh. What are you doing, Oscar? Is that tiny lump a chigger buried under your skin?”

“We will see who builds the best tent,” Oscar answered. “We will sss ... sss ... see ...”

“Maybe the English man can teach us,” Jacob said. “Maybe he can teach us to be house builders.”

“I will be too busy training to be a soldier—and working on my soccer,” Oscar said.

Jacob remembered his mother using the bark of the baobab to make rope. He and Oscar collected several armloads, soaked the bark, then braided strips into ropes, which they used to lash together pieces of wood for sturdy poles.

They used long grasses for the roof. At first, they cut their fingers on the sharp edges of the grass. “Ouch!” Willy sucked on his fingers to stop the bleeding.

“Like this, Willy.” Jacob had watched his older sisters many times, and showed the others how to hold the grass so the edges curled in while they braided it. The roof was a sparse mixture of grass, branches, plastic, and leaves when it was finished. All four boys could huddle under it to escape the sun during the day; at night, their legs stuck out as there was only room under the roof for their upper bodies. It took them a few days to scrounge enough building materials and piece them together, but finally, on the fourth night in Ethiopia, they had a shelter to crawl into as the moon rose in the sky.

“This is nice, but I am still waiting for that feast,” Oscar complained. He closed his eyes and licked his lips. “Sorghum, roasted pumpkin, chewy kisra, sticky bananas, juicy mango, and especially milk ...”

“Just imagine ... you told us Ethiopia was a country of riches, Oscar.”

Oscar shrugged. “Sometimes, not often, I am wrong, Jacob. But I am learning not to listen to Majok.”

Before bedtime, Jacob said, “Let’s go look for our families again. Maybe Louise and Matthew are here, too.” They walked up and down the rows, peering into each of the shelters, staring at the faces around the flames of the open fires.

“I don’t see any girls; no mamas, either,” Willy said. “Everybody’s a boy.”

“They must have gone to another camp,” Jacob said. “I have heard people here speak of other refugee camps.”

“We can look again tomorrow, when there is more light,” Monyroor suggested.

That night, Jacob took out his stone and held it up so it shone by the light of the full moon. Dear Mama—are you there? Is there lots of food where you are? Are there any fireflies? We are so hungry, and Willy is so skinny—he looks like sticks held together by skin. He doesn’t complain, but we can’t wait much longer ...

Jacob awoke the next morning to a steady humming sound. His brain was still fuzzy with sleep, and his eyes refused to open. It’s only Mama grinding the grain and Grandmother singing to the goats. As the noise grew louder, he opened his eyes a slit and saw Willy curled up next to him. He sat up quickly, his heart pounding. Jacob crawled out and looked to the sky first, then all around the camp. He stayed low and sprinted to an open area, away from the tents, so he could see better. He peered at the horizon anxiously, expecting to see a great line of tanks thundering across the desert, followed by angry horsemen, shouting and waving their swords in the air. He saw only a blazing ball of fire and the end of the earth.

Chapter Twelve

Jacob dashed back to the tent. Please, no, not again ... no more bombs! All around, other boys stumbled from their shelters, still half asleep and mumbling to each other as they tried to track the noise. “Wake up, Monyroor!” Jacob shook his nephew awake. They raced back to the clearing and stood close together, staring into the distance. The drone persisted and grew louder as the starry blanket of night was pushed away by the shimmering sun. For a long time, nothing appeared to disturb either the flat plain of dirt or the cloudless sky.

Finally, Jacob saw a great wall of brown smoke emerging from the edge of the earth. “Is it a fire, Monyroor?”

Monyroor stood silently, squinting and rubbing his forehead. Before long, the humming became the deep rumble of many engines. A line of white trucks soon followed, slowly weaving their way across the desert, stirring up more clouds of dust as they came. Jacob raced back to get the other boys. “Oscar, Willy—come quickly! Something’s happening!” The four boys stood in the crowd, watching and wondering. All around them, others did the same, the younger boys clinging to the arms of the older ones.

“It’s not the bad men, is it?” Willy asked.

“They’re driving very slowly. It doesn’t seem like they’re trying to attack us,” Jacob answered. “And I think they would have attacked while we were sleeping.”

“It’s the feast—I’m sure of it.” Oscar rubbed his belly.

“I hope you’re right, this time,” Monyroor answered.

By the time the dusty vehicles arrived at the camp, hundreds of fidgeting boys stood waiting. Jacob didn’t like the fiercely hungry look on some of the boys’ faces, in their eyes; he hoped there would be enough food for all of them.

“UN,” Monyroor said, reading the letters on the side of the first truck. He had learned a few English letters from his uncle in Juba. “But I don’t know what that is.” The crowd of boys followed the trucks as they drove through the camp.

“Ahhhhh ... it must be the feast arriving, at last!” Oscar said, holding his arms open wide in welcome. “It must mean ‘food.’ Think of how many bananas big trucks like that could carry!”

The trucks stopped, and two white men got out of each truck and began heaving white plastic sacks and blue jerry cans onto the ground.

“You, come here,” one of them shouted at Monyroor. The boys didn’t understand his words, but his gestures were clear. Soon the sacks and cans were being passed down a line of older boys and into the big white supply tent. The same boys were then told to follow the white men.

“Where are you going, Monyroor?” Willy asked, hanging on to the older boy’s hand. “Will you come back?”

“I don’t understand what they are saying, but they are pointing for us to follow them,” Monyroor answered. “It’s all right, Willy. Stay with Oscar and Jacob.”

Several of the biggest boys were taken to another UN tent, where a Dinka man, who also spoke some English, explained their duties.

“UN stands for United Nations. Other countries in the world have heard of your troubles and sent representatives to help you. Please cooperate and do as they ask,” he said to Monyroor and the others. “You have been chosen because you are the oldest of the walking boys. You will each be responsible for making sure your large group is well fed and cared for; you must act as their father, or uncle.”

It took a long time just to count the boys as they milled about Monyroor. Jacob helped, and the

y eventually determined there were close to a thousand in his group.

“Thirteen is very young to be a father,” Oscar said. “Where are your beautiful wives, Monyroor? You must have many to have so many sons!” He puckered up his lips and kissed the air. “Smoochy, smoochy!”

“Not now, Oscar,” Monyroor said, turning away and rubbing his gaar. “I must think.”

“He’s putting on his lion-hunting face again,” Oscar said to Jacob and Willy.

“Monyroor is a good chief. These boys are lucky to have him,” Jacob said.

The morning was spent outside the camp, lining the boys up and breaking them into smaller, more manageable groups. Friends made on the journey stood close together, making Monyroor’s job of dividing them into smaller groups easier.

“If we have about thirty boys in each group, it will be easier to organize the work,” Monyroor said.

“I can help count,” Jacob offered again.

“Thank you, Little Uncle. There are many jobs; cooking, cleaning, getting food and water, collecting firewood, building, and looking after the small boys and the sick ones. We will have more material for shelters now; I think it will be best if we build them to hold six boys each.”

“Maybe we should have some small boys and some big boys in each tent?” Jacob suggested quietly.

“Good idea.” Monyroor asked everyone to remember that the smaller boys needed older boys to look after them. “When you were small, your mamas and sisters cared for you; you must be mama and papa, sister and brother to these small boys.” Because Monyroor was a leader, he was permitted to have only three other boys in his tent; Oscar, Willy, and Jacob.

Monyroor appointed leaders within each group of thirty. Those leaders had to make sure each boy was registered at the UN tent and given a plastic identification bracelet. A boy without a bracelet would be a hungry boy without food rations.

Jacob, Oscar, and Willy stood in the hot sun, waiting for their bracelets most of that long afternoon in Ethiopia. They watched hungrily as the lucky boys ahead of them rushed away, clutching their sacks of food to their chests.

“Maize!” Willy shouted, pointing to the ground as a boy with a leaking sack ran past. As he bent down to pick up the few stray kernels, six bigger boys shoved him out of the way roughly, knocking him to the ground and snatching the morsels up for themselves.

“Majok? Did they teach you to be a vulture as well as a sss ... sss ... snake at your school?” Oscar grabbed the other boy’s arm. “Give those back to Willy; he is only little.”

“You are jealous because I already have my food, Monkey Boy.” Majok yanked his arm away. “That corn is mine. Wait your turn. Pick some fleas off your friends while you wait.”

Jacob shook his head. “They are like hyenas fighting over a dead cow.” He and Oscar each gave Willy a hand and pulled him to his feet.

“Are you all right?” Jacob asked, brushing the dirt off Willy’s purple shorts. Grinning, Willy opened his hand so only they could see the three grimy golden treasures.

“Good work, Willy! You have the sharp eyes of a raven!” Oscar said. Sucking slowly on the hard kernels of maize helped their waiting time pass more quickly.

They returned at sunset to find Monyroor busy giving orders to his group leaders. Already some who were about the same age as Monyroor were beginning to argue with him.

“We are too tired—we’ve been standing in the hot sun all day. We want to eat,” one boy complained. “Now!”

“It will be very difficult for you boys to eat when there is no fire to cook the food,” Monyroor said patiently. “The ground sorghum will not taste very good unless it is made into porridge.”

“Humph!” the other boy said, stomping away. “Who made him the chief?”

“Oscar, you and Jacob go out and find some sticks and dung for us to build a fire. It will help keep the mosquitoes away, and we can prepare some food—finally,” Monyroor said. Other boys were already at work, building stronger shelters with the new supplies the trucks had brought.

“He thinks he is so important.” Oscar glanced back over his shoulder and scowled as they hurried away.

“He is helping us, Oscar. Be nice,” Jacob reminded him. “I am tired, too.” The sky was the gray-blue of dusk when they finally came upon a stand of scrawny acacia trees. Oscar climbed high up in the branches, tossing bits and pieces of bark and twigs down to Jacob. When they had as much as they could carry, they stacked it on their heads.

“How do our mothers carry so much wood at once?” Oscar struggled to stabilize his load with his good arm, the crooked one held out for balance.

“It’s only our first time—we’ll get better after we’ve done it a hundred times,” Jacob answered.

“Oh, thank you, Jacob. That makes me feel much better.”

Monyroor stood with his hands on his hips as they approached. “Where have you been?” he demanded as they dumped the wood on the ground in front of him.

“Stop your roaring. We thought we would take a long walk, just for fun,” Oscar answered. “We haven’t walked enough lately, and we’re really not very hungry.” Monyroor stared at him for a few seconds, then turned his back and continued working on a shelter with some of the other boys.

“With all these people, do you think the wood was just sitting close by, waiting nicely for Oscar and Jacob to find it?” Oscar said to Monyroor’s stiff, angry-looking back.

“We’re sorry it took us so long, Monyroor.” Jacob drove an elbow into Oscar’s side. “I know we are all hungry, but the food will taste even better because we’ve waited so long. Porridge will taste so good, Monyroor, after all the leaves and grass we’ve eaten.” His nephew’s shoulders relaxed, but he did not turn around.

The second time the supply trucks arrived, they carried clothing as well as food. The boys lined up once again and waited patiently for the workers to unload bags of t-shirts and shorts. “My old shorts are too small,” Willy said. “Or maybe my belly is too big now that we have food sometimes!” They hurried back to their tent to change out of their tattered old clothes.

“If only there were some girls around to see how handsome we are now.” Oscar strutted like a rooster in his clean red shirt and brown shorts.

“We must keep our old clothing,” Monyroor said. “We may need it sometime. Willy is growing so fast—soon your old clothing will fit him.”

Jacob smiled. From looking at his friends, he knew that he, too, was no longer a stick boy. He ran his hands over his spotless gray t-shirt, then shoved them deep into the pockets of his blue shorts. He rubbed his stone between his fingers. Can you see me, Mama? Your handsome son, Jacob?

As they did each morning, the boys took turns preparing breakfast. Then they gathered wood and swept the floor of their tent with a scratchy broom Jacob had made by tying some bulrushes together. “If only Mama could see me now,” Jacob said, flexing his arm. “Feel this muscle!”

“It only looks big because your arm is so skinny,” Oscar answered.

“Want to arm wrestle?” Jacob asked, flopping down on his belly with his elbow on the ground, his clenched fist shoved in the air.

“Not until my arm gets better,” Oscar said, looking away and rubbing his bent elbow.

“How about me?” Monyroor lay on the ground across from Jacob with his arm in the air.

Jacob laughed. “Maybe next year.”

“Soon there will be no time for arm wrestling,” Monyroor said. “We will be too busy going to school.”

“What do you mean?” Oscar asked. “We’re already too busy working.”

“We’ll find the time,” Monyroor answered.

“Why will we go to school?” Willy asked. “Majok is the only person I know who went to school, and he is a mean boy.”

“I don’t think I’ll go to school,” Oscar said. “I will stay here, instead. I must work on my soccer skills if I am to be a star. School is for sissies.”

“Who will cook the food and fetch the water?” Ja

cob asked. “Will we be called bushmen, like Uncle Daniel was at school? Will they teach us to be soldiers?”

“We will all go to school,” Monyroor said firmly. “The aid workers say we must become educated so we can become leaders when we return to Sudan. They say if we can read, we can learn to be better farmers, hunters, and fishermen. We can learn to build things, like schools, hospitals, and water wells for our own villages. We can learn about the rest of the world and how things are done in countries of peace. They say we must learn to settle our problems through talking, not war. Like our grandfathers, and their grandfathers before them.”

“You sound like Mama, Monyroor,” Jacob said, grinning. “I thought you didn’t like school.”

“That was true, but now I am a leader, and I must help the younger boys to make good decisions that will help them when they return to Sudan.”

“Humph!” Oscar muttered to Jacob through a mouthful of sticky porridge. “When we return to Sudan—he’s dreaming; I’m not walking that far—ever again!”

Looking around the camp, Jacob wondered where the school would be—there didn’t seem to be a tent anywhere nearly big enough for all these boys.

Several mornings later, they followed Monyroor to a huge baobab tree on the edge of the camp. With its many fine branches, it looked like it had been stuck in the ground upside down. A small, black man in the clothing of a white man leaned against the tree, his short arms crossed in front of him. A plain silver cross hung on a strip of leather around his neck, and he was holding what looked like a piece of dry white hyena dung in his hand.

“I will be your teacher,” he said in Dinka, smiling as the boys seated themselves on the ground in front of him. “Please call me Matthew.” Jacob thought of his elderly friend from so long ago.

This Matthew showed his students the spot where he had scraped a strip of bark from all around the tree and painted it black. He had hollowed out another baobab, painted it with pitch, and filled it with clean drinking water. The boys sat silently in the shade of the tree, watching as Matthew drew strange figures on the blackened tree with the white stick, which he called chalk. “This is my name,” he said, pointing to the squiggly lines behind him. “m.a.t.t.h.e.w. I am here to help you all learn to read. Can anyone tell me why it is important to be able to read?”

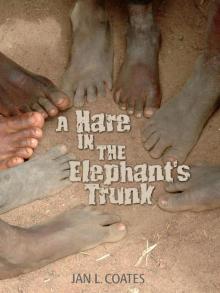

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk