- Home

- Jan Coates

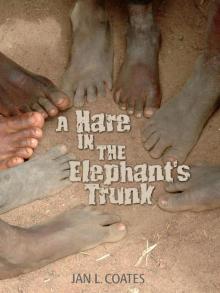

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk Page 11

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk Read online

Page 11

“When they reached the other side of the river, Elephant used his trunk to lift Hare from his back. In doing so, he accidentally cut off Hare’s tail. Hare scampered off, and when he met other hares, he told them they, too, should cut off their own tails at once or Elephant would be very angry with them. Because the hares were very scared of Elephant, they obeyed Hare and cut off their own tails.

“Elephant quickly discovered that his honey had been replaced by stones, and went angrily in search of the tailless Hare. To his surprise, every hare he came upon was without a tail, and he was unable to tell which hare had eaten his honey. He left immediately because he was embarrassed to have been outwitted by small, clever Hare. And now, my story is finished.”

Jacob was careful to thank the storyteller before leaving school.

“I liked that story today, about Elephant and Hare, didn’t you?” Jacob asked as the boys walked home.

“It was all right, but it wasn’t a very funny story,” Oscar answered.

“I mean, I liked the part where the small hare was smarter than the big elephant. Didn’t you?” Jacob said.

Oscar shrugged. “My jokes are better. You just liked it because the hare was smart, like you, Jacob.”

“Well, at least we know why hares have such small tails,” Willy said. “Compared to other animals, I mean. Is that a true story?”

Jacob shrugged. “It might be.”

Adam also continued to visit the school as part of a group of SPLA soldiers. The boys paid very close attention on those days, especially Monyroor. Adam usually chose him to be the demonstrator. Teacher Matthew remained very quiet as the men showed the students how their guns, Kalashnikovs and AK-47s, worked, and gave them drills to practice in the event of an attack.

“When you return to Sudan, if you hear an Antonov engine overhead, you must immediately throw yourself to the ground, face-first, and put your hands on the back of your head, without thinking. Yell, ‘Hit the dirt!’ so the others will do the same. When you leave Pinyudo, to go to the river garden or to look for firewood, don’t ever take anything shiny with you—the sun reflecting off it will make you very visible to people in an airplane. At all times, you must try to blend in to the earth.”

“Will the planes be able to find us here in Ethiopia?” Jacob asked. “I thought we were safe here.”

“Anything is possible with those devils,” Adam answered.

“Keep your shiny treasures in your pockets,” Jacob whispered to Willy.

“Now, this is fun!” Oscar said, throwing himself onto the ground every time the soldiers made loud engine noises. “Learning to be a soldier is much better than learning to read.”

“I am sorry, but my bones don’t like this game,” Willy said, groaning as he picked himself up slowly. “I don’t think I would make a good soldier.”

“It is good that the soldiers are teaching you how to stay safe,” Matthew said after the men had gone. “But please remember, there are alternatives to war. In many parts of the world, men talk, rather than shoot, to resolve their problems.”

“The bad men who attacked my village did not seem interested in talking,” Oscar said. Other boys mumbled their agreement.

“This war has been going on for many years in Southern Sudan; in fact, even before you were born,” Matthew said. “As you know, too many people have been killed. There must be a better way.”

As they walked home from class, Jacob asked, “Does Adam remind you of an elephant?”

“His necklace does,” Willy said.

“No, I mean he looks angry all the time. I think it’s his small eyes,” Jacob said.

“That reminds me of a funny story,” Oscar said.

“Tell us, Oscar. I love funny stories,” Willy said.

“One day, Lion decided to make sure he was still the King of the Beasts. He went into the forest and came upon Antelope. ‘Who is King of the Beasts?’ he asked. ‘Why, you are, of course,’ Antelope replied. Lion asked the same question of Warthog, Raven, Zebra, and Hyena. Their answers were all the same.”

“Didn’t he ask Hare?” Jacob interrupted.

“That’s not part of the joke,” Oscar said impatiently. “Stop interrupting. Now, where was I? Oh, right. Finally, Lion came upon Elephant, who was taking a bath in the river. ‘Who is King of the Beasts?’ Lion roared. Elephant picked Lion up in his trunk and bashed him back and forth against a tree, finally dropping him in the dirt. Lion dragged himself to his feet, shook away his dizziness, looked at Elephant, and said, ‘Well, if you didn’t like the question, you only had to say so!’”

“I get it; that’s a funny one, Oscar,” Willy said, snorting with laughter.

“But maybe the King of the Beasts should be the smartest animal, not the strongest, most powerful one,” Jacob said. “Maybe Hare is actually the King of the Beasts.”

“It’s only a joke, a story, Jacob. Don’t be so serious,” Oscar said. “I hope Monyroor made us something good for supper.”

Chapter Fourteen

Jacob loved the weeks he was on kitchen duty, especially since it meant he missed school. He lined up with the other cooks to receive his group’s rations of oil, corn, beans, and lentils. The boys had soon learned that the rations rarely lasted for two weeks. Jacob did his best not to use too much too soon.

He trekked to the small river and waded into the center in search of the cleanest water, then filtered it through a tshirt from the UN tent. Horror stories of great invisible guinea worms as long as snakes, entering boys’ stomachs through dirty water, were enough to keep him filtering until the water ran clean and clear as rain.

He continued to spend time with Mama and kept her stone in his pocket, but most days he had little free time for thinking.

Dear Mama: I am a happy cook this week. Today I stood in the river with my spear, like Aweil Longar, for a long, long time (remember the Papa-Fish story?), trying to catch a fish—a surprise for Willy and Oscar. Just when I was getting very tired and my feet were very cold, I saw two dead fish sparkling in the sun, belly-up on the water. What a lucky day! I knew they were safe to eat—they could not have been dead for long—another boy would have already taken them. I carried them under my shirt on the way home so the sun wouldn’t shine on them and show the Antonovs where I was. The boys will be so happy when they get home from school!

Mama wouldn’t recognize me, Jacob thought, as he worked to organize the meals. I have grown since the night of the bombs. Monyroor is almost a man now. Jacob’s thoughts drifted home while he stirred the simple stew over the fire pit or pounded the grain with his pole. He still day-dreamed of great feasts ... sweet potatoes, pumpkin, eggs, bananas, mangoes, roasted bushbuck ...

When supplies were very short, Jacob ventured farther away from the camp in search of food. Sometimes he happened upon an undiscovered tamarind tree and collected its plump seed pods, full of sticky sweet manna to add to his stew. One evening, he found a beehive, hanging high in the branches of an acacia tree, far from Pinyudo. The buzzing bees surprised him, causing him to fall out of the tree. He landed hard on his knees, making it difficult to run as they chased him most of the way back to camp. He marked the spot in his mind and, recalling Mama’s advice, he returned in the heat of the day when the bees were away collecting pollen. Tea with honey was a rare and tasty treat for all of them.

“Tell me a story, please, Jacob,” Willy asked that night.

Jacob rubbed his bruised knees and laughed. “It so happens I had an adventure today that gave me a new story, Willy.”

“Oh, good!” Willy snuggled into his blanket and waited.

“This is an ancient event. Many moons ago, there was a young elephant named Abu, who thought he was stronger and more clever than all the other elephants.”

“His name should be Majok,” Oscar interrupted. Jacob and Willy laughed.

“Each and every one of Abu’s teeth was a sweet tooth. Even his tusks! He had been away to school, in a city, where there were as many treats

as he could eat. When he returned, he was eager to show the others how smart he had become.

“‘I will find a sweet treat for you, my friends. I saw a very big hive on my walk yesterday, high in the branches of an acacia tree. While I am out walking this evening, I will visit the hive again. I know the bees will be away, collecting pollen while the sun is sleeping.’ Even though the others thought he might be wrong, they were very excited by the idea of a treat, and sat down to wait eagerly for his return.

“Well, when Abu arrived at the acacia tree, he listened very carefully but heard only the wind whispering in the leaves. ‘The stupid bees will be very surprised to find their hive empty when they return,’ Abu said to himself. He tiptoed up to the tree and stood watching the hive for several minutes. Seeing no activity, he stretched his long trunk up, up, up and stuck it straight into the opening in the beehive. Immediately the air was filled with angry, buzzing bees. They were even more angry than usual because they had worked hard all day, and their peaceful sleep had been disturbed.

“They chased Abu all the way back to where his friends sat, patiently waiting for their treat. Imagine their surprise when they saw, not a pot of sweet honey, but instead, a trumpeting Abu, thundering by as fast as he could go, with a great roaring black and yellow cloud of angry bees swarming after him, stinging his gray flesh every chance they got. Abu was so embarrassed, he stumbled to the river, sank into its cool water and stayed there, hiding, until the bees gave up waiting for him and returned to their hive. Ever since that time, big elephants have been most fearful of tiny bees, and they will walk many miles to steer clear of a beehive. And now, my story is finished.”

“But what happened to Abu?” Willy asked.

“He never returned to his village. He moved far, far away, and he never ate honey again!”

“You are more clever than Abu, Jacob,” Willy said. “You knew the bees would be busy during the day.”

“Indeed,” a voice said from the darkness. Teacher Matthew stepped into the light of the fire. “You are a talented storyteller for one so young, Jacob,” he said.

“I learned from my grandmother,” Jacob answered. “She is the storyteller for my village.”

“When you have learned to read and write, you can record her stories, write them down,” Matthew said.

“But Dinka stories do not need to be written down. They are always passed on by storytellers,” Jacob answered.

“Perhaps ...” Matthew said. “I hope to see you boys in school more often. Goodnight.”

Unfortunately, the Black Days came, no matter how careful Jacob was with their rations; there was simply not enough food to last for two weeks until the next shipment arrived. The boys were often hungry.

“Majok says the SPLA soldiers are stealing some of the food intended for Pinyudo,” Oscar announced.

“It’s true that Adam and the others do not look like they are going hungry. Something must be feeding their muscles. But Majok is likely wrong about them—they say they are here only to help us,” Jacob said. “I will ask Monyroor.”

His nephew was firm in his defense of the soldiers. “That could not possibly be true, Jacob. They are dedicating their lives to freeing Sudan for us, for all of us, so we will have a home again, someday. They are our friends, not our enemies.”

“Majok is often wrong; probably he is wrong this time, as well,” Jacob said.

The following week, when he was collecting firewood outside Pinyudo, Jacob noticed Adam and several other SPLA soldiers lounging about under some trees. They were laughing and wrestling, but they appeared to be waiting for something. Jacob lowered his firewood carefully to the ground, then quickly ducked behind some thorn bushes. Adam’s voice thundered across the open plain, like a trumpeting elephant.

“Hungry, boys?” The soldier punched his own hard stomach, then pointed to the horizon. “Not for long!” The other SPLA soldiers laughed and snorted as a tell-tale trail of dust in the air announced a new arrival.

Jacob soon saw a single white relief truck, driving slowly toward Pinyudo. When it reached the soldiers, the men leapt up and stood in front of the truck, guns in hand. Jacob crouched lower and held his breath as they yanked the driver out, shoved him to the rear, then forced him to unlock the wide doors. Several soldiers climbed in while the driver stood with his back against the truck, his hands high in the air as two of the soldiers pressed their rifles to his throat.

From the high pitch of the driver’s voice, Jacob could tell that he was pleading with the soldiers. The men began tossing food sacks out to the others waiting on the ground. When they had all that they could carry, they slung their rifles over their backs and ran off, hooting and hollering. The driver hurriedly slammed the doors, got back into the truck, and sped off toward Pinyudo.

From the direction of the river, Jacob saw Teacher Matthew ambling toward the soldiers, a sturdy walking stick in his hand. Jacob could hear him whistling, see the sun glinting off his cross. I hope an Antonov will not also see it. Most of the soldiers ignored the teacher and continued on their way, joking and pushing, shoving and bumping each other like a herd of goats, but Adam stopped to speak to him. Jacob could make out only some of their words, but he could not mistake what he saw.

Matthew was smiling, as usual, and he began gesturing, pointing toward the sacks of food in Adam’s arms and those being carried away by the soldiers. “I thought the truck was delivering that food to Pinyudo,” he said.

“Most of it will go to the camp.” Adam dropped his load, then stood with his feet wide apart, rubbing the elephant teeth on his necklace as he spoke. “But we are hungry, too.”

“But you are grown men. You are able to get food of your own. That food is destined for the hungry boys in Pinyudo who have no other way of obtaining it.” Matthew held up the palms of his hands, as though pleading with Adam to be reasonable.

Adam leaned forward, slipped his gun strap over his head, stood the brown rifle butt on the ground, and leaned the long, black barrel up against his leg. He crossed his muscular arms and stared down at Matthew. “And what are you doing to save Sudan? You draw pictures on your little board, and spend all day with children.” Adam stabbed one finger into Matthew’s chest, driving him backwards, toward Jacob’s hiding spot, as he continued shouting. “This is not your business. You are only a teacher; you are doing nothing to save your country. We soldiers are real men, and real men must eat well to stay strong for Sudan.”

“But, please understand; it is like elephants stealing food from baby hares,” Matthew insisted. The teacher looked very small beside Adam, but he did not back down under the soldier’s fierce glare and kept his shoulders square and his head up.

“You know nothing,” Adam roared. He threw his head back, then spat on the ground between Matthew’s feet. “You know only books; you are a coward who knows nothing of war.” He yanked the silver cross from Matthew’s neck and flung it high in the air, in the direction of the departing soldiers. Matthew jerked back slightly and put out his hands to catch his balance, but still he did not flinch.

Run, Matthew. Don’t you see that he’s going to hurt you? Jacob wanted to call out to the teacher. He tried to open his mouth, but fear clamped his teeth tightly together. He stayed silent, squeezing a branch, unaware of the sharp thorns digging into his flesh.

As the two men continued arguing, Jacob could see Adam’s rage building, making him seem even bigger, just as he had watched Majok’s anger grow so many times. Matthew walked carefully to the spot where his cross lay in the dirt. As he bent down to pick it up, Adam charged at him from behind, raised the butt of his rifle and slammed it into the back of the teacher’s head. The sound was like a lion crunching bone. Matthew crumpled silently to the ground and lay motionless.

Jacob sucked in his breath, then clapped a hand over his mouth. Adam looked around quickly, picked up his load of food, then raced off to join the other soldiers.

Chapter Fifteen

As Jacob crouched, waitin

g for Matthew to move, his stomach lurched, and he tasted a sour pool of bile at the bottom of his throat. He stayed hidden in the bushes, sucking on his bloody fingers, watching as his teacher stirred, then crawled to where his walking stick lay in the dirt. Matthew used it to pull himself to his feet, then staggered a short distance, rubbing his eyes. He bent to pick up his cross, stuffed it into his pocket, then turned and shuffled back toward camp. Even from a distance, Jacob could see the massive swelling growing on the back of Matthew’s skull. Blood oozed from the spot where the blunt force had split the skin.

Jacob looked once more at the disappearing soldiers, making sure they were too far away to see him, then emerged from behind the bushes.

“Are you all right, Teacher?”

Matthew looked at Jacob in surprise. “Jacob. Where did you come from?”

“I saw the whole thing. Your head—it’s bleeding. Can I help?” Jacob asked.

“Perhaps I could lean on your shoulder, if you don’t mind,” Matthew said. “I am a little dizzy.”

They walked in silence for several minutes. “I don’t think the soldiers are the talking type,” Jacob said finally.

Matthew smiled at him weakly. “I tried, Jacob. At least I tried. Oh! Pardon me.” The teacher hunkered down and put his head between his knees, belching loudly several times as he clutched his stomach. Jacob turned away when Matthew began throwing up, groaning in between the splashes. When his stomach was finally empty, he wiped his mouth on his sleeve, then stood and kicked dirt over his vomit. “I am sorry, Jacob.”

“Are you all right?” Jacob wrinkled his eyebrows in concern.

“I will be. I must have a concussion; my brain got shaken around, I think.”

“But why did you try to talk to Adam? Didn’t you know he was going to hurt you? Adam is so much bigger than you.”

“I am not a fighter, Jacob. Never have been, even when I was a boy, like you. But I have seen the way things work in other parts of the world. When talking, not fighting, is the normal course of things, it works. I hope someday it will work for us as well. We have to start somewhere. That is why I became a teacher—so I could help young people learn a better way to solve their problems, have better lives.”

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk