- Home

- Jan Coates

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk Page 12

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk Read online

Page 12

“Mama used to tell me I must go to school to have a better future,” Jacob said. “Maybe that is what she meant. She did not want me to become a soldier.”

“Your mama sounds like a very wise woman, Jacob.” Matthew patted Jacob’s shoulder. “Thank you for helping me. Don’t worry; I will be fine after I lie down for a while.”

“But we have to tell somebody about the SPLA. They can’t steal our food and not be punished,” Jacob said.

“Who would we tell, Jacob? The soldiers from Sudan are the ones in charge of liberating and protecting us. They are frustrated by the war and, sadly, we cannot prevent them from doing what they want. Thank you again for coming to my rescue.” The teacher smiled, then hobbled off in the direction of the school.

Jacob said nothing to his friends when he returned to the tent. As he lay in bed that night, he couldn’t get the incident out of his mind. I know the SPLA are here to help us; I know they are trying to make Sudan safe for us again. But why would they steal our food? And why would Adam hurt Matthew? Matthew is not a fighter; he is a talker. It is hard for words to fight guns ...

Matthew was absent from school for several days; when he returned, he wore a bandage wrapped around his head, but he said nothing of the confrontation. Jacob, too, remained silent. But he knew he would not be so happy to see Adam and his friends the next time they came to Pinyudo. If they are here to help us, we should not be afraid of them ... It turned out that Jacob did not have to worry about seeing Adam again, not in Pinyudo, at least.

The next afternoon, as school was winding up for the day, Matthew asked Jacob to stay behind for a few minutes. He was no longer wearing the bandage, and the bump was only slightly visible now, but the lumpy scar was almost as long as his gaar. “Please wait here, Jacob—I’ll be right back.”

When Matthew returned from his tent, he was carrying many pieces of paper in one hand.

“Is that a Bible?” Jacob asked.

“This is a storybook, the one my mama gave me when I first learned to read,” Matthew said, passing it carefully to Jacob. “You are a good storyteller. I know you will take very good care of this for me.”

Jacob opened the hard black cover and looked at the first page. The paper was very thin, like dry papyrus leaves. He turned the pages slowly—each of them was covered with letters. There were hundreds of letters altogether, some big, some small. Maybe thousands. Some pages had pictures as well, intricate black and white designs. “But what will I do with it?”

“Why, of course, you will learn to read the stories, Jacob.”

“Thank you, but I don’t think I will have time for all that reading.” Jacob reached out to give the book back to Matthew. “I will be too busy training to be a soldier.”

“I think you will surprise yourself—and make your mama happy. I already know you like stories, and you are a bright boy. One day you will become curious enough to want to read these English words.”

“Is this the only storybook, Teacher?”

Matthew looked confused; his eyebrows joined together. “The only storybook?” He paused, then said, “Ah ... I understand.” He knelt in the dirt in front of Jacob and looked into his brown eyes. He put his hands on Jacob’s shoulders. “There are more storybooks in the world than there are boys in Pinyudo Refugee Camp—can you believe that, Jacob?”

Jacob’s mouth dropped open. His eyes opened wide. Then he laughed. “But you are telling me a joke, Teacher,” he said. “There are too many boys here to count!”

“No, Jacob; it is the truth. There are as many books in the world as there are stars in the African sky. Isn’t that amazing?”

“Thank you, Matthew.” Jacob clutched the book to his chest. “I am very busy, but ... um ... maybe I will have time to look at it.” When he was out of Matthew’s sight, Jacob tucked it up under his t-shirt. I don’t want Oscar to see this—I must keep it hidden ... he would laugh at me if he thought I was learning to read. Back at the tent, Jacob wrapped the book in a grain sack, dug a hole underneath his mat, and buried it deep in the dirt.

“Come Jacob, play anyok with us,” Oscar pleaded, dancing around in front of his friend, juggling a bumpy brown gourd with his bare feet. “We have a whole hour before afternoon class.”

“Yes—physical education is a big part of school,” Matthew said. “A strong, healthy body equals a strong, healthy mind. Maybe I will also play, when I get back from my tent.”

“I will be a captain,” Majok said.

“Of course, you will.” Jacob rolled his eyes at Oscar.

The boys divided into two teams; each team had a number of long sticks sharpened like spears. One team rolled a gourd, trying to get it past the other team before it was speared. Jacob was quick; he had to be to avoid getting a spear in one of his big feet!

Jacob rolled the gourd up the rough field and bounded along behind it. Majok charged at him from the side and stepped on his foot hard, pinning it to the ground, almost tripping him. Jacob caught his balance and tried to shove him away, but Majok, who was bigger and heavier, refused to budge.

“No fair,” Oscar called. “No stepping on the feet allowed!” He grabbed Majok by the arm and tried to pull him away.

One of Majok’s teammates put his head down and butted Oscar in the stomach while another player stole the gourd and won the game for his team. “You slimy snake! Didn’t you learn to play fair while you were at school, Majok?” Jacob hopped on one foot and rubbed his other bruised one as he went to help Oscar. “It must have been a very bad school.”

“Quack! Quack! Your duck feet are so big, Jacob. They got in my way; that’s all.” Majok leaned into Jacob with his shoulder, knocking him to the ground.

Just at that moment, Matthew came around the corner. “You are right, Jacob. Fighting is not the best way to solve problems. Head butting is fine—for goats; they are unable to talk. Come here, Majok. Sit with us for a while, and talk,” Matthew said. “The rest of you boys keep playing.”

Talking didn’t get you very far with Adam, Jacob thought. Majok and Adam could be brothers ...

Majok stared angrily at the ground and kicked up clouds of dirt. He crossed his arms in front of him, stuffed his hands under his armpits, and glared at the teacher.

“Would you like it if Jacob or Oscar stepped on your foot during a game? Would that be fair, Majok?” Matthew asked.

“I suppose not. But his feet are so big—they get in the way!”

“Is it Jacob’s fault his feet are big?”

Majok shrugged.

“-Do you like your feet, Jacob?” Matthew asked.

“Most of the time, except when Majok makes fun of them. The rest of the time, I like them because they make me fast.”

“Do you agree not to step on Majok’s feet during your next game?” Matthew said.

“If he agrees not to step on mine.” Jacob laughed. “It sounds silly when you say it like that. But if he hurts me, I get to hurt him back.”

Even Majok had to laugh. “I will do my best to follow the rules, Matthew. Anyok would be no fun if everybody’s feet were pinned to the ground.”

He quickly changed his tune as they walked back to join the others. “You are like a hare only because you are timid as a hare, Jacob.” Majok snorted noisily, then spat a great glob of mucus in the dirt at Jacob’s feet. “You are a crybaby.”

Jacob looked at the green glob, then stared at Majok for several seconds. “Is that snake poison, Majok? Will you shed your skin next? Maybe underneath, you are a nice boy.” Without waiting for a reply, Jacob ran to join Oscar on the sidelines. The two friends stood together, talking and laughing, as they waited for a new game to start.

“Are you two crybabies playing, or are you too chicken?” Majok called out.

“Let’ssssss ... go!” Oscar grinned at Jacob as he strode onto the field.

Majok picked up the gourd and carried it to center. The other boys took their places; Majok began rolling the gourd, racing behind it up the field. Jac

ob and Oscar sprinted ahead, then suddenly lunged at him from either side. They each stuck their spears out at the exact same time, stabbing them into the gourd, sending Majok sprawling face-first in the dirt.

“Sss ... sss ... sorry!” Oscar shouted, as he raced away and thumped the gourd into the goal. He and Jacob jumped into the air, slamming their chests together in a victory dance.

“You cheaters! You’re dead meat next time, Jacob and Oscar,” Majok yelled as he picked himself up and limped off the field, spitting out a mouthful of dirt. “No fair, two against one. Leave me alone,” he said, shoving his teammates away. “They won’t get away with this ...”

“Majok isn’t the talking kind of boy,” Jacob said. “He only understands fighting.”

“He’s not tough enough for us, though,” Oscar said, flexing his muscles. “Hey, I have an English joke. What kind of animal would Majok be, if he wasn’t already a snake, that is?”

“I don’t know—an elephant?”

“No, a cheetah—get it? I just made that up, right now. Pretty good, huh?”

“Funny, Oscar. Very funny. Ha ha ha!”

That night, Jacob lay inside the tent, looking up through a jagged hole in the roof. When he was sure the others were asleep, he pulled Matthew’s book out from beneath his mat. His lips moved as he tried to shape the words in the storybook by the light of the moon. He studied the strange pictures. There is a cow and a jug, some millet, and people telling stories around the fire—just like home. Clouds wisped along in front of the moon like puffs of gray smoke. Jacob rolled over on his side, leaning on one elbow as he puzzled over the words and pictures, absentmindedly rubbing his Mama stone. His mind kept drifting home. As the seasons passed, it was becoming harder to picture his family. Was it Abiol who had the space between her teeth, or was that Adhieu? My big sisters must be as tall as Mama by now. Maybe Adhieu is a mama, too! And Sissy, she is no longer a baby ...

In the morning, Jacob woke up smiling, positive he was back in the mud hut curled up between his sisters. He could hear their soft voices telling stories of Papa, stories they told to help him know the brave man Jacob did not remember, the gentle giant. But when he opened his eyes and looked up through the triangle hole, yellow sunlight was already pouring into the tent. Everything outside the opening was a brilliant blue, and the only story being told was of Oscar’s snoring.

If I was home, the baobab leaves would be fighting the sun, keeping us cool. And Mama would never allow a hole to stay in the roof!

Jacob looked at the sleeping boys all around him. He stared at his dried grass knots on the tent pole closest to his sleeping mat. Thirty-six—the moon has grown full above us thirty-six times in Ethiopia, but I still cannot hear the stars singing, Mama. These snoring boys are my family now; I am lucky. I am going to school; I am starting to learn to read, and you would be surprised at how good I am now at looking after myself. But I am forgetting the smell of groundnut stew cooking, the rustling of Grandmother’s wrinkled hands weaving grass, the music of your grinding song ... where are you, Mama?

PINYUDO REFUGEE CAMP, NOVEMBER 1991

“Life is good, don’t you think?” Monyroor said, one cloudy morning as they sat sipping hot sweet tea for breakfast.

“You are right,” Willy said. His eyes sparkled again now that he had food and water almost every day. His head looked the right size for his body, and it was no longer possible to count his ribs. His face was rounder and his brown eyes did not look so huge as they once had.

“When will we go back to Sudan?” Oscar asked. “I am getting tired of waiting for my family to find me. Three years is too long. I want Mama to see how good I’m getting at soccer.”

“You said you would never walk that far again,” Jacob reminded him.

Oscar frowned at him. “That was before,” he said. “A long time ago, Jacob.”

“If only we had a rainmaker here,” Willy said. “My toes are tired of dirt. They want grass again.”

“We must be patient,” Monyroor said. “One day at a time. Every week, more and more people arrive here, refugees from Sudan. The war goes on without us. It is still not safe in our country. I have heard rumors of troubles in Ethiopia now as well. I hope they are just rumors.”

The clouds gathered quickly into a great rumbling mass. It began to drizzle before the boys left for school. Everyone in camp stood outside for a few minutes, faces tilted to the sky, letting the cool water wash over them, sucking the dry dust from their pores.

“I think a rainmaker somewhere heard your wish, Willy,” Jacob said. They huddled inside their tent and prepared for a quiet day of mancala and rest. Jacob tried to fix the Purple Raven while the other boys drew pictures in the dirt. Monyroor tootled on the pipe he’d made from a bushbuck horn he’d recently been given. He still had a lot to learn. It’s almost like a rainy day at home, Jacob thought lazily.

The drumming of the rain on the roof had just softened to dripping, and Jacob was half asleep, when the peaceful morning was shattered by the pounding of many feet splashing through the camp and violent shouting. “Attack! Attack!” Jacob’s heart thumped wildly as his mind jumped back three years. He sprang to his knees, covered his ears, and closed his eyes.

“What is it, Jacob? What’s going on?” Willy shouted above the noise. Jacob opened his eyes, jumped up, and grabbed the little boy’s hand.

BOOK IV

Chapter Sixteen

“Take everything you can carry!” Monyroor barked, rushing outside to help his other boys.

“Do we hit the dirt?” Willy asked. “Like Adam taught us?”

“I don’t hear any engines,” Jacob said. “But you must be fast, Willy. Quickly!”

“I’m sorry, Jacob. I’m hurrying as fast as I can.” Willy struggled to stuff his few belongings into a sack.

When they had gathered together their clothing and what little food and blankets they had, they stepped outside. At the last minute, Oscar stuffed the Purple Raven into his bundle. Jacob grabbed their only pot. Outside, hundreds of boys streamed away from the camp. As they waited for Monyroor, Jacob glanced back inside to make sure they hadn’t forgotten anything.

“Wait here, Willy.” Jacob ducked back inside the tent and dug frantically at the warm spot on the floor where his mat had been moments before. He grabbed an empty plastic grain sack and shoved Matthew’s storybook inside it.

“Hurry up, Jacob!” Oscar cried. “Monyroor says we have to go—now!”

“Follow me!” Monyroor commanded over the noise. He bent low and veered away from behind the swarm of fleeing, mud-splattered boys. Jacob squeezed Willy’s hand and tried to help the little boy keep up with Oscar and Monyroor. They ran and ran, their feet slapping against the muck until Willy stumbled and fell.

“I’m sorry, Jacob. I can’t keep up.”

“Climb on my back, Willy.” Jacob bent down to help him up. Willy clasped his muddy hands around Jacob’s neck and wrapped his legs around his waist.

They ran, then walked, then ran some more until darkness fell and they could see nothing. The older boys took turns carrying Willy.

“At least ... now we are ... bigger,” Oscar said, panting. “And stronger. I feel like ... I could run ... all the way back to Sudan.”

“That is exactly what we must do,” Monyroor said. “The Ethiopians are chasing us out of their country. They know we must cross the Gilo on our way. I’m sure they will be waiting for us there.”

“Why don’t we just stay here then?” Willy asked.

His question was answered by a sharp popping sound in the shadowy trees, followed by screams of agony from somewhere in the darkness.

“We must keep running,” Monyroor said. “Let’s go.”

At daybreak on the third day, they joined the mob of people racing toward the river. Jacob was breathing heavily, and his heart pounded in his ears. Above the splashing and thudding of hundreds of feet, Jacob heard a noise overhead that made him shudder. It sounded like giant hornets whining t

hrough the air. Only this time, he knew the hornets’ nest had a name—Kalashnikov. Jacob held on tightly to Willy’s legs and forced himself to run faster; he was gasping for breath when they finally arrived at the River Gilo once again. The other side looked just as far away as it had three years before.

They crouched low and sloshed their way to a skinny part of the river; blinding sheets of rain slapped at their bare skin. The tall grasses along the bank had been beaten down by the torrential rain and the gusting winds, but the river itself was high and fast. Willy clung to Jacob’s hand. His thin arms trembled. “It’s roaring like a hungry lion,” he whispered. “I’m sorry ... I ... I ... I don’t think I can do it ...”

Monyroor bent close to Willy’s ear. “We’ve done this before. We can do it again,” he said calmly. “You’re a big, brave raven now, Willy. Pretend we are flying across the river.” His smile looked tight and forced. “Jump on, Willy.” The small boy closed his eyes and climbed onto Monyroor’s broad back. They made their way to the narrowest part of the rapidly rising river and stepped in cautiously. The smelly muck oozed up around their knees, making loud sucking sounds as they lifted their feet. This time there were no crocodiles in the water—they were lying along the bank on the other side, waiting, watching with half-closed eyes. Bullets continued to whine overhead as shouting, angry Ethiopian soldiers herded the boys toward the wild, rushing river.

Jacob and Oscar stuffed their bundles up under the backs of their t-shirts, then tucked the t-shirts into their shorts. They made the spider, locked their fingers together tightly, then followed Monyroor and Willy into the water. “Don’t let go!” Oscar yelled above the noise of the guns, the wind, and the rain. He did not look brave or strong as the water churned violently around them, making it hard to keep their strokes smooth and even. Jacob struggled to hold his head above water and keep his elbow linked with Oscar’s at the same time. All around them, other boys fought to stay afloat.

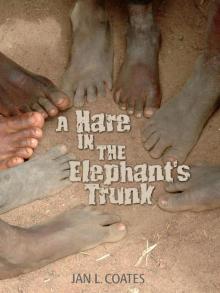

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk