- Home

- Jan Coates

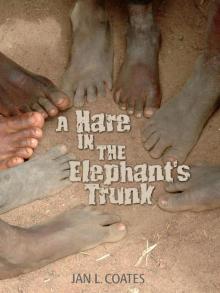

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk Page 17

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk Read online

Page 17

After several months, Chol decided his students were ready to write the primary level exams. They spent all of two days taking exams in reading, writing, science, social studies, and math. Finally, a chance to write on paper with a pencil, and to erase my mistakes completely, Jacob thought. He was careful to check each of his answers before passing in his exams. A few weeks later, the boys arrived to see a long, neatly printed list posted above the blackboard.

“Your name is at the top, Jacob!” Oscar called out. “And Willy’s name is here, and look, there’s mine; we all passed!”

“You are the teacher’s little pet, after all, Jacob.” Majok leaned over Jacob’s shoulder. “No wonder your name is at the top.”

“But you came third, Majok. Why are you complaining?” Jacob asked.

“I am smarter than you, Jacob. I was feeling sick on the examination day,” Majok answered.

“Of course you were,” Jacob answered.

All that day, Jacob had a warm, tingling feeling inside his stomach. “You go ahead,” he said to the others when school was over. “I’ll catch up.” He needed to be alone to try and figure out the feeling. Am I getting sick? Did a worm not get boiled out of the water? Is it eating me up? He squeezed his stomach with both hands as he walked. He hadn’t thought about Mama or the war all day; he’d been too busy listening and learning. Then it struck him. I’m happy! I’m excited! This is what it feels like to be happy! I know there will be a tomorrow for me, a better tomorrow—and I will go to school, find answers to all my questions and learn to read many stories!

“You look like a little girl, Jacob. Like Sissy. Why are you prancing like that?” Majok shouted, as Jacob skipped by him. Majok was still sulking.

“I am happy, Majok. Do you know what that feels like? I don’t think you do.” Jacob smiled and continued skipping all the way to his tent.

When time allowed, the boys continued to look for their families. Each time Jacob met someone from the Bor District of Sudan, he asked eagerly after his mother. Some people knew of his family, but no one had heard any news.

Jacob continued slowly working his way through Matthew’s Dinka storybook, and he read the stories aloud to anyone who would listen. Oscar was most often on the soccer field. He had made new friends before they’d arrived. They were rough boys who liked to wrestle and play jokes. There was no sign of Teacher Matthew, but Jacob took good care of his book and kept it wrapped in plastic and buried in the dirt floor of their tent when he wasn’t using it.

Teacher Chol had traveled and lived in other parts of the world. He had many stories to share with his students. “Do you know what snow is?” he asked, one especially hot day.

A chorus of “no’s” answered his question.

“Isn’t that what the wind does?” Majok asked, looking smugly at the other boys.

“You’re thinking of the word, ‘blow,’ Majok. Snow is like sand, but white and sparkly, and very cold. In places like Canada and the United States, it falls from the sky, like rain, during the winter season. Children play in it and build snow people from it; it’s sticky, like mud, only cleaner. Giant machines, called plows, are used to clear it from the streets.”

“Like tanks?” someone asked.

“A little bit, but not as violent. Plows are useful machines, not destructive machines,” Chol answered.

One morning, Chol brought several large pieces of paper with him to school. The paper was covered with tiny letters. “This is a newspaper,” he said, holding it open. He pointed to a black-and-white picture. “Look.”

“That’s us!” Jacob cried.

“Let me see—where am I?” All the students crowded around, trying to find themselves in the photograph.

“Is that you?”

“I’m sure that is Majok! See how his mouth is wide open, like he’s yelling orders?”

“The faces are too small to tell who they are,” Jacob said. “But who made this picture of us?”

“A newspaper is used to spread information around the world,” Chol explained. “A person in America, a reporter who writes stories for this newspaper, took that picture of you boys with a camera as you walked to Kakuma. Many people all around the world have read about you in the newspaper. You are all famous!”

“But who is this?” Oscar pointed to a picture underneath theirs.

Chol laughed. “That is also a famous person—the King of Pop, Michael Jackson. He also lives in America, and he is a very rich singer and dancer.”

“We are also singers and dancers,” Willy said. “But we are not rich.”

“Not yet,” Oscar said. “But maybe someday.”

“Anything is possible,” Chol said. “Because of this newspaper article, people from many countries are sending help for you; food, clothing, medicine, and money. They are calling you ‘The Lost Boys.’”

The boys all looked at each other in confusion. “But we are not lost; we are in Kenya, in Kakuma Refugee Camp,” Jacob said.

“That is a good point, Jacob. There is a very famous English story about a boy who never grows up. It is called Peter Pan. In that story, there are many orphan boys, abaar, boys living without parents, who are called ‘The Lost Boys.’ I suppose that is why the newspaper is calling you the Lost Boys as well; you are also living without parents,” Chol explained, “... unfortunately.”

“You were really a lost boy, Oscar,” Jacob said, as they walked home.

“Never—I always knew exactly where I was and where I was going,” Oscar insisted.

“I think I would rather be a found boy than a lost boy,” Willy said.

“If this was a game of Seek and Find, we’d definitely be the winners—nobody has found us for a very long time,” Jacob said.

“A very, very long time.” Willy laughed.

“Chol says there are many parts of the world where it is always peaceful, places where there is never war,” Oscar said.

“Just imagine ...” Jacob said. “Maybe someday ...”

Chapter Twenty-Three

Refugees continued arriving at Kakuma from Southern Sudan, and gradually, more and more of the older boys left to join the Sudan People’s Liberation Army. Several times each month, soldiers and commanders marched into camp to recruit boys from Southern Sudan. The thudding of their heavy boots in the dirt as they marched around the seated boys caused Jacob’s heart to pound. Willy pressed himself up against Jacob’s shoulder.

“It is your duty to save Southern Sudan—do you want to live in Kenya forever?” the men shouted. “We must fight to get back our country! Sudan forever!” As the months passed, Jacob noticed Oscar listening with more and more interest to these recruitment speeches. His friend admired the soldiers’ long rifles and asked many questions about their work. Oscar was already as big as some of the young soldiers.

On their way to school one morning, the boys met a soldier from Oscar’s village. He was not much older than Oscar and Jacob. “You go ahead,” Oscar said to Jacob. “I must talk to Kwol.” Oscar did not arrive at school that day. Jacob had trouble concentrating on his lessons, wondering where his friend could be. He remembered how Monyroor had disappeared during the night.

When his friend returned at suppertime, Jacob asked anxiously, “Where were you, Oscar? I was worried about you.”

“I was talking to Kwol about joining the SPLA. He said I am too young and that my arm could be a problem. He said it would be difficult for me to hold a heavy gun.”

Jacob tried not to show his relief as he shared his friend’s disappointment. “I am sorry, Oscar. But, anyway, we didn’t want to lose you again so soon.”

“We have all been away from Sudan for a very long time; I don’t want to live in this stupid refugee camp for the rest of my life,” Oscar said. “We will be worth nothing if we don’t have any cattle. Who would want to marry us?”

“Are you getting married, Oscar?” Willy piped up.

“I am only twelve, Willy. I don’t own even one ox.”

�

�I don’t want to stay in Kakuma forever, either,” Jacob said. “That’s why I want to go to school, like Chol and the other aid workers. Did you know there are places in the world where everybody goes to school? Chol says they are often the same places where there is no war. I want that for my country.”

“That sounds like a lot of slow, boring work, and a lot of time, Jacob,” Oscar said. “I want to join the soldiers now to make sure our country survives. I want quick action—zip, zip ... not slow thinking and talking. When we have saved Southern Sudan from the northern monsters, we will all be able to return to our villages. Then we will have time to worry about education.”

The boys stared into the fire. Jacob stirred the coals with a stick. He didn’t want Oscar to become one of the rough soldiers. They scared the small boys when they came into camp with their loud, angry voices, scowling faces, and huge rifles.

“Please don’t leave us, Oscar,” Willy said. “We need you to keep us laughing. Kakuma would be very boring without you.”

“Hey, that reminds me of an English joke, Willy. What do cows like to listen to?”

“Um, birds singing?” Willy said.

“No, Moooo-sic!” Oscar answered.

“That’s not very funny, Oscar,” Jacob said.

“Don’t you get it, Jacob? Moooo-sic?” Willy laughed so hard he fell over.

“You are too serious, Jacob,” Oscar said. “Willy needs my jokes. For now, I will stay. Maybe when I am older, and my arm is fixed, I’ll go. I will concentrate on my soccer skills until then.”

Jacob paid extra close attention in school the next day. As he watched Chol and the other adults who had been to school, working hard to help the people in Kakuma, he became more and more convinced Mama had been right. The only way to end the violence was to teach people, to show them other choices, help them learn to talk and work together, like the aid workers, instead of against each other like starving, wild animals feeding on hate.

Several weeks after the first exams, Chol asked Jacob to stay behind after school. “You did very well to place first in the primary school exams, Jacob. The Red Cross is looking for someone to work as a translator, someone who can speak both Dinka and English, and maybe some Arabic. You have been very quick in picking up English, reading, writing, and speaking the language. Would you be interested in that work, Jacob? You would be paid, only a small amount, but a small amount is better than nothing.”

“Oh, yes, Teacher, of course. Most certainly, I am interested.” Jacob’s eyes sparkled. He began working for a few hours after school each week, translating for the aid workers as they communicated with the Dinka people in the camp.

“Please, can you ask them why my mother is taking so long to find me?” One small boy came almost every day that Jacob worked.

“I am sorry, Isaac. The workers have written a letter to your village, but there has not been an answer yet. Letters are like turtles—they move very, very slowly.” Jacob bent down and looked into the little boy’s eyes. “But I am sure your mama is thinking of you all the time. I am also waiting to hear from my mama.”

“Can you ask them again?” The little boy pointed a grubby finger at the Red Cross workers at the table behind Jacob. “Please?”

“Excuse me, Thomas. Have you had a response from Isaac’s mother, yet?” Jacob asked.

The man shook his head. “Not yet. Maybe next week. When you are finished with Isaac, could you help me with this list, Jacob?”

“Oh, yes, please.” Jacob grinned. “I would like to use your pencil.”

Jacob often had to explain to people why they were unable to return to their villages in Southern Sudan. “The war is still there,” he repeated “It is not yet safe in your village.” No one had an answer to the question of when the war in Sudan would be over.

Jacob buried his shillings carefully in the dirt beneath his blanket each month, along with his book and ration card.

“What do you do when you’re at work?” Willy asked, watching Jacob hide his earnings one evening.

“I am helping Dinka people who cannot speak English communicate with the aid workers,” Jacob replied. “I try to help them with their problems.”

“That sounds like an important job,” Willy said.

Jacob shrugged. “I am lucky that learning is easy for me, that’s all.”

When Jacob reported for work one day, he was surprised to see Majok lying in a bed in the Red Cross medical tent. His eyes were covered with gauze bandages.

“Do you have a problem, Majok?” Jacob stopped beside his cot.

“Is that you I hear quacking, Duck Boy?” Majok lifted himself onto his elbows and turned his head in Jacob’s direction. “They say I have trachoma—my eyes are infected.”

“I thought you only had pinkeye, like Oscar,” Jacob said. “What is trachoma?”

“It is very serious.” Majok’s voice trembled as he lay back down and covered his bandages with his hands. “They say I m ... m ... might go blind.”

Jacob reached out and touched Majok’s shoulder. “I am sorry, Majok.” The older boy rolled over, swatting Jacob’s hand away.

“Can I help you?” Jacob asked. “It must be very boring here.”

“Yes—just leave me alone,” Majok replied. “Go back to your books and your crybaby friends.”

Jacob stood silently for several minutes, watching Majok’s shoulders shake as he cried quietly. Finally, Jacob tiptoed away.

The following afternoon, he returned to the Red Cross tent. “I brought my book of Dinka stories,” he said. “Would you like me to read to you, Majok?”

“Why would you do that?” Majok asked.

“I need practice reading English out loud,” Jacob answered. “That is all.”

“All right, then. It’s true that you stumble over a lot of words.”

“Of course it is.” Jacob read for almost an hour. When it was time for supper, he asked, “Would you like me to come again tomorrow?”

“You really do need more practice,” Majok answered.

Jacob returned every day for a week. Each day it appeared Majok was growing stronger. Eventually the gauze was removed from his eyes.

“This itching is making me crazy.” Majok dug at his eyes with his knuckles.

“At least your eyes are getting better,” Jacob said. “Will you be back at school soon?”

“Of course. You need someone to compete with,” Majok answered. “Someone to make you study harder.”

The boys missed Monyroor, but otherwise life went on as usual at Kakuma. Majok recovered; spring turned to summer; autumn turned to winter. When summer came around again, some of the aid workers started an Activities Group to entertain the children; boys with too much time on their hands turned to fighting for entertainment.

Dear Mama: I wish you could see the playground we are building. The teachers are helping us. Even Majok is helping us. We made seesaws by laying tree branches across plastic water drums. Last week, I showed the teachers how to make toy trucks by nailing tin cans to boards. One of the workers said, “You are as clever as a hare, Jacob!” I am still your little hare, Mama. Only now I am big.

The squeaking of the car wheels and the seesaws blended in with the delighted squeals of the children. Jacob and Oscar collected scraps of plastic, thin sticks, and packing string, then worked with the smaller children to turn them into kites, patchwork bits of brightly colored happiness flying over Kakuma. An aid worker showed them how to use the flat, circular lids off plastic containers to play catch. “Frisbee,” he called it.

The group organized soccer games, anyok competitions, and games of kak. Willy had very quick reflexes which made him an excellent kak player. He could easily pick several pebbles off the ground with one hand and still grab his stone out of the air before it returned to the earth.

When they raced home now, there were times when Willy almost caught Jacob.

“I am turning into a hare, just like you, Jacob!” the little boy said triumphantly. �

��Look at my big feet!”

“So you are, Willy.” Jacob laughed. “Only my feet do not look so big now that I am taller.”

One day, a large box arrived from Japan. Chol showed the boys the label, which read: For The Lost Boys of Sudan. Inside, the boys found many flat pieces of black-and-white rubber. “But what do we do with them?” Jacob asked. “Are they flying discs, Frisbees?”

“No, not exactly,” Chol said. “But they are for fun.” He removed a long tube with a hose from the box and showed them how to use the air pump to blow up the balls.

“Real soccer balls!” Oscar picked one up, ran his fingers all around it, tracing the seams, then squeezed it and dropped it. “It bounces!” He set it carefully on the ground again, took a big run and kicked it, as hard as he could. They all watched with delight as it sailed high up into the blue sky. “Now I will be a soccer star!” he shouted, running off to retrieve it.

For Jacob, the next surprise was even more exciting. Chol arrived at school one morning carrying another large carton. He opened the top to reveal stacks of green notebooks and bundles of long, yellow pencils with pink tops. Chol cut the scribblers in half and gave each student half of a scribbler and one pencil.

“May we take these home?” Jacob asked, his eyes shining as he printed his name neatly on the front of the notebook. “Are they for us to keep?”

“Yes,” Chol said. “You can practice at home. The pink squishy part is an eraser; instead of scratching mistakes out in the dirt, you can use it to correct your mistakes in the notebook.”

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk