- Home

- Jan Coates

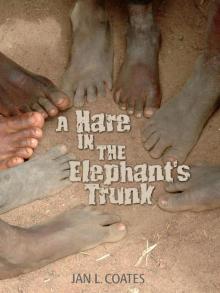

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk Page 18

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk Read online

Page 18

“Like on our exams,” Willy said.

“Of course—I forgot you have already used pencils,” Chol said.

“But who has sent these wonderful things to us?” Jacob asked.

“Children at a school in the United States collected money to buy these notebooks and pencils for you, after they read about The Lost Boys in the newspaper,” Chol said. “Their letter says, ‘We have great respect and admiration for your ability to survive in such harsh conditions and your desire to go to school. We hope these things will help.’”

“It seems the newspaper is a most useful tool.” Jacob grinned. “Almost as useful as a cooking pot or a spear! Maybe I will be a newspaper reporter someday. I could write about the war and ask people to help us stop it.”

“That sounds like a very good idea, Jacob,” Chol said.

Jacob carried his notebook and pencil home, wrapped them carefully in the grain sack with his story book, and hid it under his blankets. What will I write? Hmmm ... He paced back and forth outside the tent, thinking about it for a long time, while the others were off playing soccer. I know many more Dinka stories than the ones in Matthew’s book; Grandmother’s voice is still in my head ...

Finally, Jacob dug out his scribbler and began to write. He wrote and wrote and wrote until the light became too dim to see by, and his letters started to look more like scribbles than letters. When Oscar and Willy returned, his notebook was almost full; its pages curled up with the weight of his words, a mixture of Dinka and English. His arm and fingers were stiff and aching. I didn’t know I had so many words, not until I started to write them down.

Willy wrapped himself in his blanket and curled up on his mat. “Tell me a story, Jacob?”

“I will read you a story tonight, Willy.” Jacob opened his notebook. “It has both Dinka and English words. This is an ancient event ... In the early days of the earth, Warthog was a handsome beast, but he was also rude and boastful. He was a little lazy, as well, and often took old anteater holes to use for his home. One morning, he was on his knees, grazing on roots and grasses and wallowing in the mud. He was so busy filling his belly that he didn’t notice Porcupine ambling along, looking for a quiet place to rest. She crawled into Warthog’s burrow, where she fell fast asleep.

“Warthog did, however, notice Lion, and couldn’t help making a rude remark about Lion’s messy mane. Lion was tired of Warthog’s ignorant behavior and began chasing him. Warthog scurried back to his den and crammed himself into the tunnel. Porcupine woke up and, fearing an invasion, prepared to attack with her long, sharp quills. In the darkness, Warthog slammed into her, ending up with a face full of pain.

“He shot back out of the tunnel and pleaded with the other animals to help him remove the quills. They were all fed up with his rudeness and refused to help him. His face became lumpy and swollen, and he was sore for many days as he tried to work out the quills himself.

“From that day forward, Warthog’s face has been covered with warts and bumps. But he is no longer rude, keeps to himself, and always, always backs into his home. And now, my story is finished.”

“Finally, the Warthog story, from our first walk,” Willy said. “Thank you, Jacob. Is your scribbler full of stories already?” He leaned over Jacob’s shoulder. “How do you know so many words?”

“Think how many exciting true stories we’ll have to tell our families when we find them,” Oscar said.

“Someday, I hope to write down some of our stories, things that happened since we left home, I mean.” Jacob glanced quickly at Oscar to see if he would think his idea was stupid.

“You are a storyteller, after all, Jacob,” Willy said. “Your stories would be good in books.”

“Even I might like to read such stories,” Oscar said. “If I am to be the hero, of course! You could call your book The Magnificent Monkey Boy Oscar!”

“I was thinking something more like Jacob the Clever Hare,” Jacob said.

“Nah ... my name is better. Your story was all right, but I have a new English joke. What happened when the lion ate the joke teller?” Oscar asked.

“He started laughing?” Jacob guessed.

“No ... he felt funny!” Oscar said. “Get it?”

“Good one, Oscar,” Willy said, but he laughed only a little before falling asleep.

“Wait, one more. What kind of story does a hare like at bedtime?”

“I don’t know, Oscar. I’m too tired,” Jacob answered sleepily.

“One with a ‘hoppy’ ending. Get it? ‘Hoppy,’ not ‘happy’ ...”

By the next night, Jacob had filled two entire half-scribblers with his favorite Dinka stories, stories he remembered Grandmother telling around the fire. I wonder if Grandmother is still on earth. She would be surprised to see her stories written down, especially in English. Many of the Dinka words didn’t have a match in English, but he did his best. He showed them to Chol the next day.

“I know there are many mistakes—could you help me fix them?” Jacob asked.

“Of course! Then you should read these to the small girls and boys. It will help them with their English and also help them learn traditional African stories. So many of them have no parents or older siblings to tell them such stories,” the teacher said.

Now I am a translator and also a writer, Jacob thought. All because of school ...

Jacob continued to write letters to Mama, too, sometimes in his head, but sometimes in his notebooks. He began keeping track of the date.

September 12, 1993

Dear Mama: Oscar is becoming very muscular and a strong soccer player, even with his crooked arm. He does exercises every day, trying to get it straight again. Willy and I listen to the elders talking about Southern Sudan, and we go to school and church every day. I wear a cross around my neck now, just like my teachers. I am becoming a writer of books ...

As Jacob’s collection of filled notebooks grew bigger and bigger, his hope of seeing Mama on earth again became smaller and smaller. In his dreams, he saw her gentle face clearly, but in the bright light of day, her face became blurry and fuzzy around the edges, and her voice was a soft whisper he could barely hear.

Newspapers continued spreading the word about Kakuma, and building supplies arrived more frequently. For one whole month, the boys took time away from school and worked together to build a school of tall grasses and wood.

“Designing and planning buildings is a job for some people,” Chol said as he and Jacob worked together, tying up bundles of grass. “Architects and engineers get paid a lot of money to design houses, office buildings, and schools in cities. They also design water systems, bridges, and roads.”

“But how do they learn to do all these things?” Jacob asked.

“There are schools called universities where people learn to be doctors, business people, teachers, engineers, and architects—there are many, many courses to study. In Nairobi, not far from here, there are many boarding schools where boys like you study in preparation for going to university.”

“Are the schools like our fine new school, Chol?” Jacob asked.

The teacher laughed. “They are full, solid buildings, Jacob. Made of brick and steel and concrete, with roofs and windows. Maybe you can go to boarding school one day.”

“I would like that very much,” Jacob said. “But I have no cattle to pay for school.”

“If you want it badly enough, you will find a way, Jacob. Wadeng.” Chol winked at him. “Keep saving your translation money.”

The first Kakuma school did not even have walls, but the students could finally study away from the glare of the sun. In 1994, a real school building, with a roof, was constructed from clay bricks. The students sat on benches, and Chol wrote on a chalkboard. But there continued to be few teachers, and many, many students. Refugees continually flooded into the camp; it seemed all of them were sick of war and hungry for school.

Eventually, a library was built. Jacob was first in line on the day it opened. He walked i

nto the small, dark room, stood in the middle of the floor, and turned around slowly, staring at the dozens of books on the shelves. Teacher Matthew was not joking. Where do I start? The first book he picked up was about Africa. It had many glossy photographs as well as words. He sat down on a bench and began reading. Each visitor could stay for only a few minutes as the library was very small, and many people wanted a turn.

Every night, Jacob rushed to the library right after supper. He began copying out some of the words in the books so he could study them again at home. He was hard at work one evening when he felt someone reading over his shoulder.

“Trying to make sure you place first in the exams again?” Majok sat down beside Jacob on the bench.

“I am just interested, that’s all,” Jacob said.

“In what?” Majok looked at the cover of the book. “Giraffes and elephants?”

“Well, this book says that Africa is an enormous continent— that Southern Sudan and Kenya are only small parts of Africa.” Jacob glanced sideways at Majok, expecting the older boy to make fun of him. “I wish they had a map of Africa, so I could see how big it really is.”

“Let me see.” The two boys sat, shoulder to shoulder, reading about Africa until their turn was over.

“Can you believe there are hundreds of different languages spoken in Africa?” Majok asked as they walked home. “And we know only two?”

“Can you believe there are millions and millions of people living in Africa?” Jacob said. “And we are only two?” They both laughed.

“If that is just Africa, the world must be enormous!” Majok said. “I don’t think there is a number big enough for all those people.”

“Maybe tomorrow we can learn about America—the place our notebooks came from,” Jacob suggested. “And could you help me with my math? I do not understand when the numbers and letters are mixed together; algebra, Chol calls it.”

“Oh, that is easy. If you help me with my English verbs, I will help you,” Majok said.

Jacob smiled. Maybe Majok is growing up, learning to live in cieng. That is the first time I can remember him being nice to me. Our fight seems a very long time ago—we are competitors in school now, but that is good competition. Maybe we are learning to respect each other ...

The following morning, Jacob noticed a small boy at the window opening of the school. The boy ducked down when he saw Jacob watching him, but his fingertips clung to the windowsill. Jacob looked back to the front and resumed listening to Chol, but out of the corner of his eye, he remained aware of the small boy’s head popping up and down in the window. After class, Jacob looked around the corner. The boy began running away when he saw Jacob coming. “Wait!” Jacob called, holding his empty hands up in the air. “I only want to talk to you.” The boy hesitated, then stopped and waited for Jacob to catch up to him.

“Do you live in Kakuma?” Jacob asked.

The small boy shook his head and pointed to the desert outside Kakuma.

“Are you Turkana, then?” Jacob asked.

The small boy nodded and looked fearfully at Jacob, who smiled warmly in return.

Jacob pointed to himself and said, “Jacob.”

The little boy pointed to himself and said, “Lokaalei.”

Jacob tried speaking in Arabic, and the boy nodded and seemed to understand some of what he said. “You come back tomorrow. You want to learn English?”

Lokaalei nodded his head enthusiastically. “English. I come with sun tomorrow.” He pointed to the sky.

Jacob smiled again and waved goodbye.

The following morning, Jacob arrived at school early. Lokaalei sat waiting for him outside the school. Jacob spent an hour with the boy, teaching him the alphabet, using a stick and the dirt.

When Chol arrived, Jacob said, “Chol, this is Lokaalei—he would like to go to school. Is it possible for him to join the primary class?” Jacob stood behind the small boy, who beamed up at the teacher.

Chol smiled at Lokaalei, looked at the boy’s wrist for a Kakuma bracelet, then shook his head sadly. “I’m sorry, Jacob. He is not registered as a refugee with Kakuma officials. Only refugees can go to school here. Is he Turkana?”

Jacob nodded, then tried to explain to Lokaalei in Arabic what the teacher had said.

The little boy’s face fell, and he turned as if to run away. “No, wait,” said Jacob. “I will meet you, out there.” Jacob pointed to a scrub tree in the desert, just beyond the school. “Tomorrow morning?”

Lokaalei nodded and scurried off between two tents.

“I’m sorry, Jacob. But there are already too many students in Kakuma, and not enough teachers. And there have been problems with the Turkana stealing from the refugees here.”

“I understand, Chol. But maybe I can help him sometimes.”

For several days, Lokaalei appeared faithfully just after sunrise, and before his own classes, Jacob continued teaching him the alphabet. Then, one day, Lokaalei didn’t come, and although Jacob looked for him each day, the little boy never showed up again.

“The Turkana are nomads, Jacob,” Chol explained. “They must travel constantly to find grazing land and water for their goats and camels. But at least you helped Lokaalei for a short time. If he is so eager to learn, he will find a way.”

Chapter Twenty-Four

The days went by quickly. By the time Jacob had been in Kakuma for almost three years, many older boys, including Oscar, had stopped attending school. But Majok had carried on with his schooling, and he and Jacob remained fierce competitors for the highest marks.

One morning, Jacob overheard Majok and some other boys talking. “They are going to close this rickety school,” Majok said casually. Jacob dropped his pencil and stared at Majok. All of a sudden, it seemed like a boa constrictor was squeezing him around the chest; he felt as if he were being smothered.

“That can’t be true!” Jacob said, after he’d caught his breath. Somehow, Majok often heard Kakuma news before the other boys, and his news was usually accurate. “But why?” Jacob rubbed his ears, swallowed several times, dug his teeth into his lower lip, and blinked hard.

“There are not enough teachers and too many students. Haven’t you noticed, Jacob? You’ve been too busy writing your little stories, studying, and working for the Red Cross,” Majok said.

“Chol has seemed very tired lately,” Jacob said.

“My family has sent money for me to go away to school, boarding school in Nairobi,” Majok bragged. “You will need to find someone else to help you with math, Jacob.”

“But how much money do you need?” Jacob thought of his small pile of shillings.

“About three thousand,” Majok replied.

“Three thousand shillings?” It might as well be three million, Jacob thought. “That is a lot of money.”

“My father’s family has also sent money,” another boy said. “Finally, we will leave dry, dusty old Kakuma and go to real school with real teachers and classrooms with strong walls, new textbooks, and lots of paper.”

“But we have books and paper here,” Jacob interrupted. “We have learned so much together in our library, Majok. It has helped us do well on our exams; we have done well, even compared to students in city schools.”

“We each have half a notebook at a time.” Majok held his up by one corner. It was tattered and torn, and covered with scribbles and cartoons, unlike Jacob’s notebooks, which were always clean and well-organized. “And those English books—they are older than the teachers!”

“I cannot tell you for certain, Jacob,” Chol replied, when Jacob asked about the school closing. “I hope it will not happen.”

As Jacob trudged home that evening, he barely heard Willy chattering along beside him. I want to go to such a fine school, too, he thought. I cannot stay here if they close the school. But I have no money. I’m not even sure if I have a family anymore. Are you there, Mama? Can you help me think of a way to go to school? There must be something I can do ...

&

nbsp; Jacob slept fitfully for several nights, and each time he awoke, he sat bolt upright, panic causing his heart to race. I must go to school ...

A week later, Chol confirmed the bad news. “I have tried my hardest to persuade the officials that we can keep the Kakuma school open, but they have decided to close it—there are simply too few teachers,” he said. “I am sorry, but there is nothing else I can do.”

Jacob stayed behind after class. “I must go to school, Chol.”

“I know that is true, Jacob. I wish I could help you,” the teacher replied. “This is a very big problem for a young boy.”

“I may be only thirteen years old on the outside, Chol, but I am so much older inside.” Jacob smiled. “I will give my problem some more thought.”

“Remember, every problem has at least one solution. Wadeng, Jacob Deng. Wadeng ...”

Jacob tossed and turned on his mat as he tried to think of a way to get to school. One morning, he woke up even before the rooster. He looked around at his sparse belongings: Matthew’s book, a small pile of shillings from his work, several notebooks, fifteen full and one empty, two t-shirts, two extra pairs of shorts, one sweater, two blankets, one blue school bag—still quite new. My belongings must be worth something ...

“Did you hear about those people, greedy relatives of Col Muong, who got caught by the purple light?” Oscar asked at breakfast.

“What happened?” Willy asked.

“Two men returned to Sudan to sell their belongings. When they came back, they got a second ration card.”

“Did they get kicked out of Kakuma?” Jacob asked. “How much money did they make?”

Oscar shrugged. “I’m not sure.

“It doesn’t matter,” Jacob said. “The purple light always catches them; maybe they won’t be allowed back in to Kakuma.” Would I be ready to leave Kakuma, all by myself? What if I needed to come back?

“What are you thinking about?” Willy asked through a mouthful of porridge. Jacob sat staring into space, rubbing his ears and contemplating. Think, Jacob. Think! He stood up and paced back and forth in front of their tent. Am I brave enough?

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk

Hare in the Elephant's Trunk